- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Agnes Martin and Jackson Pollock were both born in 1912, but Pollock had died by the time Martin moved from New Mexico to New York in 1957 to establish herself as a painter. Martin came at the behest of Betty Parsons, one of many women artists whom Parsons took under her wing as the fervor of Abstract Expressionism faded. Many of these women deferred their artistic careers until midlife, after families or more traditional careers—Martin herself was a teacher. Throughout her life, Martin maintained a principled independence as an artist, existing outside the politics and ideologies of the art world. The only exception was the period between 1957 and 1967, when she lived in New York. Her work became well known under the patronage first of Parsons and then Virginia Dwan—gallerists who represent her importance for Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism, respectively. Parsons gave Martin her first solo show in 1958, and by 1966 Martin’s paintings hung alongside factory-fabricated sculpture by Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, and Carl Andre in a definitive show of Minimalist art, Ten, at the Dwan Gallery. But by 1967, as Martin told a friend, “I had established my market and I felt free to leave.”1

This decade, Martin’s only sustained stay at the center, is surveyed in a modest selection of paintings at Dia:Beacon. The exhibition “. . . unknown territory . . .” follows “. . . going forward into unknown territory . . .”, and is the second installment in a planned four-part retrospective of Martin’s career. These first two shows survey Martin’s oeuvre from 1957 to1967, and the current exhibition differs only in the subtraction of three canvases from the original installment and the addition of five new ones. There is no discernible shift in focus implied by this recalibration; rather, its sameness reflects the persistence and subtlety of Martin’s careful, handmade grids, at which she labored for nearly five decades until her death in December 2004. Dia:Beacon does not address this unusual exhibition strategy, though the format ascribes an experiential value to Martin’s paintings; like the Rothko Chapel, historical narrative is dispatched in favor of a further-reaching, intangible significance that is also suggested by the meditative, sanctum-like galleries.

Martin pressed forward with her remarkable feat of endurance seemingly outside of time, in willed monastic seclusion. For ten years after her departure from New York she lived in an adobe hut built by her own hands on a remote New Mexico mesa. Her harmony with nature and Zen-inspired asceticism, in which the social and material world was an obstacle to overcome, have long been part of art-world lore. Martin claimed to have no personal possessions, and in the 1990s she said she had not read a newspaper in more than fifty years so as not to clutter her mind. For her urbane collectors belonging to the moneyed, competitive New York art world, Martin and her paintings fulfilled a complex of longings and moral idealism. Martin’s rhetoric created an aura of timelessness as well; she spoke of “inspiration” in a general sense, locating herself among the ancients and the Abstract Expressionists, and alternatively insisted “I don’t believe in influence,” recalling Pollock’s famous declaration, “I am nature.”2

The earliest works on display remind us that Martin was an Abstract Expressionist. Although she admired Pollock’s “total freedom and acceptance,” her first abstract paintings are rooted in the Color Field tradition of Mark Rothko and Ad Reinhardt, with all attendant implications of humanism and secular spirituality.3 Like Rothko, she believed it was within reach to paint “abstract emotions.” But in place of Rothko’s tragic outlook—he once noted “the fact that people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures” as a sign of his accomplishment—Martin painted “about happiness and innocence and beauty." 4 An oil painting from 1957, Wheat, supplants the foreboding palettes of Rothko and Reinhardt with variations on cream and beige that intersect in a vague cruciform. Painting as a refuge for “the untroubled mind” was her pursuit: Wheat alludes to the Saskatchewan wheat fields of her early childhood, many decades and worlds removed from Cold War New York.5

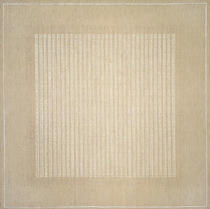

While the social terrain and the art world metamorphosed outside, Martin painted in a solitary loft in lower Manhattan with a view of New York Harbor. Her oeuvre made barely perceptible transitions. For a pair of canvases from 1959, Martin carved into a thick surface of white oil paint, in one case neatly partitioning the canvas into rows of vertical rectangles scored with graphite that mimic the irregular joints of a brick wall. In another, the surface is carved into registers containing rune-like triangles, suggesting the pictographs of Pollock or Rothko. Between 1957 and 1964, her experiments with the materiality of paint yielded to compositions in which paint, textile, and graphite have equal resonance. By 1964 Martin phased out oil paint in favor of acrylic and polymer, media that highlighted the canvas textile over the richness and tonality of paint.

Martin began painting on six-foot, square canvases in 1961; but as her compositions grew in scale, they also became miniaturist. The blocks of mellow hues in early paintings such as Wheat gave way to refined atmospheric surfaces, in which whispers of graphite and acrylic foreground the weave of the canvas. As Eva Hesse might well have noted in the mid-1960s, Martin’s compositions succeed through formal contradiction—the weave of the canvas is regular but imperfect, machined but exposing the organicism of cotton or linen. This same impasse is conveyed by her hand-drawn grids, reliant on a measuring tape but refusing the transcendence of perfect geometry. Martin noted that this imperfection caused the viewer to realize “the perfection of the mind,” which could visualize ideal forms where the hand failed. But as with Hesse’s work, this tension has rich metaphoric value beyond Martin’s preferred Platonic reference. To read past Martin’s claims of the abstract ideal, her canvases reveal artistic choices that constituted a specific stance in relation to Minimalism and the 1960s generally—they are autographic yet refuse narrative, are declamatory in their lack of statement, are richly varied while instituting the uniformity of the grid, and by making the act of seeing arduous, demand much of the viewer.

Martin succeeds best at these formal contradictions where she introduced color in extreme restraint. Grey Stone II (1961) is often used to illustrate her work from this period (as in James Meyer’s Minimalism, London: Phaidon Press, 2000), but it defies reproduction to a greater degree than most Martin canvases. Daubs of cornflower blue fill in a graphite grid drawn on raw canvas. Gold leaf that nearly matches the natural hues of the canvas has been rubbed into the surface in patches that look at first like oil stains; but on closer inspection, these discolorations glint with the richness of gold. The undifferentiated “graph paper” format of Garden (1964) also bursts with infinitesimal nuance on close viewing. The faint grid over flat acrylic is drawn with red and green colored pencils. By attempting the impossible task of hand-inscribing red and green parallel lines one millimeter apart, Martin’s lines generate surprising harmony or dissonance as they overlap and diverge. This abundance of deliberate and accidental detail is proliferated by the pencil’s continual snagging on canvas grain. The proximity required for such viewing creates visual saturation; the canvas becomes a borderless expanse with more tiny variations than the eye can register.

Dia:Beacon displays Martin’s work in three identical interior galleries that demarcate an intimate encounter. This is quite the opposite of the demands of massive sculptural installations by LeWitt and John Chamberlain that command the factory floor just outside Martin’s small rooms. The contrast is illustrative: The scale and forthrightness of artists such as LeWitt and Chamberlain shaped trends in the late 1960s that Martin defied. Illuminated unevenly by staggered skylights, Martin’s faint grids on flat acrylic create hovering fields of gray that resolve only with patience and scrutiny. It is true to her aesthetic ethos that atmospheric conditions, rather than uniform spotlighting, transform her paintings in this setting. This almost impressionist insistence on ephemeral, fluctuating visual effect is a repudiation of LeWitt’s systems or Chamberlain’s Pop-oriented incorporation of car culture. Next to their hulking steel, Martin’s canvases are nearly immaterial.

In 1967 Martin left New York for good to reside and paint in New Mexico for the remainder of her life. By this point the art world was trying to make Martin a Minimalist, but the increasingly dogmatic Minimalist program was incompatible with Martin’s approach. LeWitt turned to factory fabrication “as a reaction against the idea that art was composed with great sensitivity by the artist,” yet it is impossible to conceive of a Martin painting that does not foreground sensitivity, the personalism of the hand, and above all, imperfection.6

Kirsten Swenson

Assistant Professor, Department of Art, University of Massachusetts, Lowell

1 Jill Johnston, “Agnes Martin: 1912–2005,” in Art in America, Vol. 93, No. 3 (March 2005): 41-42.

2 Holland Cotter, “Agnes Martin,” Art Journal, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Fall 1998): 79.

3 Martin quoted in John Gruen, “Agnes Martin: ‘Everything, everything is about feeling . . . feeling and recognition,’” ARTnews, Vol. 75, No. 7 (September 1976): 94.

4 Cotter, 78.

5 Agnes Martin, “The Untroubled Mind,” in Agnes Martin (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1973): 17–24.

6 Alicia Legg, ed., Sol LeWitt (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1978), 77.