- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Visually compelling and intellectually sophisticated, Mapping Sitting: On Portraiture and Photography, A Project by Walid Raad and Akram Zaatari presented a wealth of photographic materials from the collection of the Beirut-based Arab Image Foundation (AIF). Embracing current theoretical approaches to the display of visual culture, the exhibition, curated by two artists, offered a richly textured and highly nuanced picture of Arab photography and its relationship to questions of identity. If the history of photography from this region is as little studied as the artist-curators assert, then their show certainly constitutes an exciting opening gambit that should inspire further study.

Walid Raad, the New York–based Lebanese artist widely known for work done under the name the Atlas Group, and Akram Zaatari, a Beirut-based video artist, filmmaker, and curator, collaborated on the exhibition. Zaatari is a co-founder of AIF; Raad sits on its board. Founded in Beirut in 1996 to “interpret Arab identity” and study its often-overlooked visual culture, the foundation maintains an archive of seventy thousand photographic works, most of which are commercial photographs, although there is a substantial number of amateur snapshots as well.

The fifth exhibition of materials drawn from these extensive holdings, Mapping Sitting presents itself as equal parts artist intervention and straightforward historical exhibition. Overall, the show presented visual expression as one vehicle toward articulating self-identity but rooted this narrative in the introduction of photography in the Middle East through the colonial photographers whose jobs it was to document the exotic people and places of the region for patrons back home. Having learned about the practice and technology of photography from apprenticeships in these colonial studios, Middle Easterners did not shy away from exploiting its power. Mapping Sitting takes pains to demonstrate the results when they then turned their lenses toward each other. Regrettably, the popular response to the exhibition has been to sigh with relief at the abundance of images of “good” Arabs. Such a reaction, though, ignores the intellectual underpinnings of the enterprise, which makes a sophisticated play on notions of identity politics.

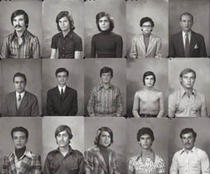

Entering the gallery, visitors first encountered a stunning wall of what Raad and Zaatari categorized as “i.d.” photographs because they were originally intended for passports or other official documents. Numbering over 3,400, the black-and-white headshots—each only a couple of inches high—were individually pinned to the wall edge to edge in a rigidly formulated grid. Reprinted from negatives once belonging to Studio Anouchian in Tripoli, Lebanon, and which originally dated between 1935 and 1970, the photographs in this large-scale installation drew in viewers to study the individual faces and the curators’ groupings of like individuals (men with mustaches, women in scarves, men with necklaces or in printed shirts). The overall patterning of light and dark also encouraged the viewer to step back and contemplate the whole. Many of the sitters looked very “Western”—lots of jackets and ties, very few chadors.

In a nearby vitrine, open pages from a bound book of original small i.d. photographs produced by Studio Soussi, which operated in Sidon (Saida), Lebanon, from 1934 to 1986, provided a historical comparison to Raad and Zaatari’s wall presentation. On each page, thumbnail headshots appeared in a similarly tight grid. Sitters’ foreheads were eerily marked with inscriptions that indexed each person for easy cataloging and retrieval. The unspecified system of organization (chronological? by photographer?) served to highlight the deliberately arbitrary, almost tongue-in-cheek classifications in the curators’ own mural composition.

Another section of the show was dedicated to the “itinerant” photography of Hashem el Madani, also of Sidon (Saida). Wall labels told his story in spare prose: Of Saudi descent, Madani learned the trade from an immigrant Jewish photographer in Jaffa and later returned to Sidon to found the studio Shehrazade, which remains in business today. Madani traveled the same route nearly every day, walking Sidon’s streets and strolling on its sandy beach. “Using a Kodak photo manual as his guide,” according to a brochure essay, “he instructed his subjects to adopt stock poses.” Series of large photographs arranged in yet another grid on the far wall showed some of these: men swimming, men (and two unexpected women) reclining on the sand or on rocks, some more naturally than others. A catalogue devoted to Madani (a separate AIF publication on view in a reading area) presents a convincing visual argument for him as an Arab Walker Evans. Indeed, his story subtly posed the question to what degree Arab self-image is formed by the technology and vision of their colonizers, even when they themselves hold the camera.

The most visually dramatic part of the exhibition was a spellbinding video made with a composite of images created in the tradition of “photo surprise”—a common practice in the Middle East between the 1940s and 1960s—in which the photographer took posed or candid shots of pedestrians on city streets and handed them calling cards advertising his studio; the subjects were invited to come buy a print or to have a formal portrait taken. The pictures montaged together here came from Agop Kyumjian’s Photo Jack Studio in Tripoli’s Tell Square and were overlaid in a manner that recalls David Hockney. On opposite sides of a screen in the gallery’s center, Raad and Zaatari projected their video-composite images of the east and west sides of the square in forty-five-second loops, featuring an overlay of sixty photographs in quick succession. A full picture of the square emerges through the sheer number of photographs, all but one in faded color, with a single photo at a time appearing in full contrast. The engrossing installation presented the image of Tripoli as a flickering panorama, like something you might see in a flipbook, bringing a moment of the city’s history to life.

For the “group” section, the artists also used a video composite technique to combine a number of portraits of military-school classes. As opposed to the quick pace of the “photo surprise” video, this work moved in slow motion, gently scrolling from photo to photo and edited to create a seamless loop. Military uniforms change as one photograph gives way to another, but the procession of stony faces and crisp garments clearly gives visual form to the enforced conformity of martial culture. It was impossible to evade a sense of sadness on reading that some of the photographs came from graduating classes of Iraqi police academies, an occupation infinitely more dangerous today.

Visitors familiar with Raad’s work, in which, as Janet Kaplan recently wrote in Art in America, “truth and fiction consort,” could hardly avoid approaching the exhibition with a measure of good-natured skepticism. Knowing some of the marvelous fictions, often involving photographs, that Raad creates in his engagement with the “hysterial documents” collected by his archival Atlas Group forces the viewer to question whether or not some of the main characters in Mapping Sitting, like Hashem el-Madani, are equally fanciful. The process of imagining that fiction could be true is one thing; looking at actual history and thinking it might be fiction is the liberating opposite of the same coin. A university gallery seemed just the place for such a purposefully ambiguous presentation.

As a case in point, consider the following exchange between a visitor to the gallery and Raad during a gallery talk with Grey Art Gallery Director Lynn Gumpert. The visitor, comparing what he described as the relatively “straight” presentation of the historical material in the grid of identity photos with the Tell Square video montage, suggested with regards to the latter: “Here you’re doing something very different. This installation reads as a work of art.” Raad’s exuberant response went to the heart of the matter. “There are different ways of producing meaning,” he insisted. “We are artists. We use images to produce experiences and feelings. Historians and writers make interventions too. We are using formal strategies to get these images to say something they would not otherwise.” And indeed, in this presentation, the materials fairly sang.

This lyrical presentation was sometimes at odds with the artist-curators’ academic language, for example, the clunky exhibition title. And I quote from the catalogue (designed by Beirut’s Mind the Gap and something of an artwork in itself): “The [photographic] practices in question are symptomatic of an evolving capitalist organization of labor and its products.… These practices were not only reflective but also productive of new notions of work, leisure, play, citizenship, community, and individuality.… Photographs functioned as a commodity, a luxury item, an adornment” (0.002). This kind of by-now familiar academic language emphasizes the individual’s position within a more powerful organizing system, such as, for instance, the grid that Raad and Zaatari employed repeatedly throughout the exhibition. In contrast, however, the exhibition drew much of its power from the sheer quantity of distinct identities that populate the images and in the richness and specificity of the stories the photographs contain. We are not solely constructed identities, these faces seemed to say. It was this particular ability to combine both the theoretical and the specific that made Mapping Sitting such a success.

Brian Boucher

Art in America