- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Meot: Korean Art from the Frank Bayley Collection at the Seattle Asian Art Museum, curated by Hyonjeong “HJ” Kim Han, celebrates Frank Bayley’s sustained admiration for Korean ceramics by framing his collection through the concept of meot—an aesthetic of balanced elegance that embraces imperfection. Presenting over sixty works spanning the Goryeo (918–1392) and Joseon (1392–1897) dynasties as well as contemporary reinterpretations, the exhibition reflects Bayley’s vision to capture Korean art’s evolution. While the exhibition gestures toward the layered complexities within Korean art, a more robust historical framework might better illuminate how shifting cultural values and aesthetic sensibilities influenced Korean art, particularly in ways that resonated with Western collectors like Bayley.

The concept of meot serves as both an interpretive framework and organizing principle, inviting viewers to appreciate Korean art’s subtlety, understated elegance, and acceptance of imperfection, developed in close association with Confucian aesthetics, which prized humility, restraint, and simplicity over grandiosity. By emphasizing meot, the exhibition not only underscores the particular qualities that characterize Korean ceramics but also draws attention to Bayley’s sensitivity to these cultural nuances with the domestic and international history of contact, innovation, and persistence in the Korean peninsula. In this way, the exhibition suggests that Bayley saw Korean art as embodying a quiet strength and beauty rooted in unpretentious forms—qualities that are not immediately striking, but resonate with a deeper sense of cultural pride and resilience.

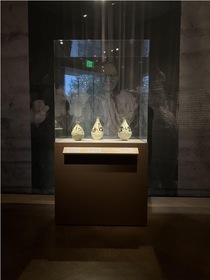

The exhibition opens with a striking display of Joseon-dynasty buncheong ware that sits between two contemporary works. Amidst this display, a Bottle with flower design serves as a visual thesis for understanding the transition of Korean ceramics during the Joseon period. In contrast to the jade-like refinement of Goryeo celadons, which prioritized smooth surfaces and translucent pigmentation, buncheong ware embodies a more expressive and folk-oriented character, marked by looser, tactile surfaces and dynamic brushstrokes. The jar’s floral motifs, rendered in the artist’s gestures in its iron pigment, convey a whimsical immediacy that diverges from the technical precision of celadon ceramics and aligns with Joseon’s literary and folk culture.

Within the exhibition, the buncheong Bottle with flower design becomes a powerful statement on the evolution of Korean art, highlighting a shift toward materiality and simplicity resonant with Confucian values. These values, emphasizing unembellished beauty and a grounded aesthetic, reflect a broader societal movement during the Joseon dynasty. This deliberate departure from the ornate stylizations of Goryeo ceramics was achieved while building upon the peninsula’s rich natural resources—namely, its abundant high-quality clay. Potters skillfully integrated these materials into a new artistic vocabulary that aligned with the ethos of Joseon society, forging a style both organically rooted and culturally resonant. Bayley’s focus on such works reflects his appreciation for the evolution within Korean ceramics from highly refined, technically complex surfaces to a more unadorned, organic aesthetic. This perspective aligns with his broader appreciation for art that communicates strength through modest aesthetics and quiet resilience. The Bottle with flower design, along with other key historical pieces in Bayley’s collection, illustrates how Korean artists moved from a focus on pristine surfaces to a more lived-in elegance, one that embraced everyday materials and a sense of immediacy.

This connection of historicity within Korean art continues through works by contemporary artists such as Yoon Kwang-cho and Kim Yik-yung, whose ceramics reinterpret traditional buncheong and baekja forms with a distinctly modern sensibility. Yoon’s ceramic vessels, with their rough, layered surfaces and spontaneous applications of white slip, evoke traditional buncheong techniques while offering a personal interpretation of Korean aesthetics as a living and evolving tradition. His brushwork recalls both Hangul and Hanja scripts, subtly nodding to Korea’s linguistic history and its complex interactions with Chinese culture. However, the exhibition does not provide much context for these linguistic influences, which might enhance understanding of Yoon’s references to Korean identity. His approach to surface and form reflects a spiritual yet assertive embrace of tradition, bridging the past with his own interpretation of Korean aesthetics as something continuously renewed.

Contemporary artist Kim’s Moon Jar offers another compelling example of how contemporary artists engage with traditional forms while subtly reimagining them. The jar’s unadorned white porcelain, a hallmark of Joseon-era Confucian values, conveys a restrained elegance that embodies ideals of purity and humility. Her reinterpretation introduces modified proportions and textures that lend a contemporary gaze to the iconic form without diminishing its historical significance. This delicate evolution from tradition to innovation mirrors Bayley’s admiration for Korean art’s capacity to adapt without losing its essence. The seemingly simple form of Kim’s jar, however, is deceptive; its soft, irregular shape demands technical precision and skill, showcasing Korean art’s dual ability to balance fragility with resilience—a duality that Bayley found deeply compelling.

While the exhibition effectively conveys its donor’s appreciation for Korean ceramics, it could benefit from a broader examination of the cultural intersections that shaped Korean art’s trajectory. For instance, Son Manjin’s calligraphic work, rooted in Chinese influences, celebrates Hangul’s unique role in asserting Korean identity. Similarly, Yoon’s inscriptions reflect the continuity of tradition while calling attention to Korea’s distinctive aesthetic heritage. However, the exhibition’s limited framing of calligraphy and language traditions misses an opportunity to explore these rich intercultural dialogues, which have historically been integral to Korean art’s evolution. By incorporating more historical context into these exchanges, the exhibition could deepen viewers’ understanding of Korean art as a narrative of resilience and cultural self-definition amid external influences.

Even as the aesthetic brilliance, technical mastery, and collector’s vision of the artworks merit attention, it is worth reflecting on the historical weight of Japanese colonial influence on Korean visual culture. During Japan’s colonial rule over Korea (1910–45), artistic and cultural practices were often subject to censorship and stylistic regulation, influencing how artists navigated traditional forms under constraint. Recognizing these colonial dynamics, even briefly, would provide valuable context, as many pieces in the exhibition reveal both adaptation to and resistance against these imposed influences. Considering these external pressures would align with an increasing trend in museums to present colonized cultures’ art within frameworks that acknowledge resilience and survival under oppression.

Through the juxtaposition of traditional and contemporary works, the exhibition captures an ongoing dialogue between Korea’s past and present. By placing these works side by side, the curatorial choice allows viewers to trace a continuous thread that highlights the adaptability and continuity of Korean art traditions. The display reveals how traditional aesthetics can coexist with and inspire modern innovation, illustrating Bayley’s vision of Korean art as a cultural lineage that transcends historical boundaries. The arrangement offers a cohesive narrative of Korean art that values its origins while celebrating its capacity to evolve in response to modernity, reaffirming Bayley’s commitment to honoring both the past and the living heritage of Korean aesthetics.

Ultimately, Meot: Korean Art from the Frank Bayley Collection at the Seattle Asian Art Museum presents Bayley’s collection as a tribute to Korean art’s unique blend of refinement and strength. By situating traditional and contemporary works alongside each other, the exhibition underscores a deep and enduring connection between Korea’s historical identity and its contemporary expression, embodied in ceramics that have survived centuries of change. Through Bayley’s legacy, the exhibition honors Korean art as a resilient, evolving form that retains its core values while remaining open to subtle innovation. Although further historical context might amplify the narrative, Meot stands as an homage to Bayley’s vision and a testament to the depth of Korean artistic tradition—a lineage as enduring and multifaceted as the high-fired ceramics it celebrates.

Inji Kim

PhD Student, Department of Art History, School of Art + Art History + Design, University of Washington