- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Before there was Central Park, there was Seneca Village: a predominantly Black community that thrived north of the hustle and bustle of downtown Manhattan from the 1820s to the 1850s. By 1857, Seneca Village was all but gone and its residents pushed out as the city seized the land for the development of a landscaped public park that would come to stretch across fifty blocks and three avenues.

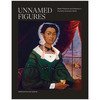

In recent years, museums around the park’s perimeter—the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Historical, and the Museum of the City of New York, among others—have sought to address the history of Seneca Village through programming, walking tours, collections highlights, and in the case of the Metropolitan, an Afrofuturist period room. These commitments have varied in their method, scope, and content, but together can be thought of as projects interested in recovery—efforts to in some way (re)materialize what the city planners of 1850s New York sought to erase. A few blocks away from the settlement’s original site, the American Folk Art Museum’s exhibition Unnamed Figures: Black Presence and Absence in the Early American North works to engage a related history of Black visibility and representation in the Northeast more broadly—a history that has long been sidelined in mainstream narratives in part because of calculated erasures like the one that happened at Seneca Village. Organized by Sadé Ayorinde, Emelie Gevalt, and RL Watson, Unnamed Figures was planned for and first presented at the American Folk Art Museum, where I saw it, and subsequently traveled to Historic Deerfield’s Flynt Center of Early New England Life.

Unnamed Figures hinges upon a two-part premise: that there are relatively few representations of Black subjects in eighteenth and nineteenth-century American art, and that when such representations do exist, these subjects tend to be presented as marginal and subordinate. And this was the case as much in the North as it was in the South, as the show’s introductory section “Looking North” makes clear with works such as Rufus Hathaway’s View of Mr Joshua Winsor’s House &c (ca. 1793–95), a so-called “house portrait” painted for a wealthy New England merchant a decade after slavery was formally abolished in Massachusetts Bay Colony. In Hathaway’s painting, a Black woman stands next to the imposing Winsor house with her back towards the viewer. Positioned between the painting’s edge and a tall gate that surrounds the house, she stands in a liminal position that might, in the broader context of the exhibition, be understood as a metaphor for the ways African Americans in northern spaces navigated a post-abolition society in which they were at once free but confronted with myriad forms of disenfranchisement and racism.

With upwards of one hundred objects and portraiture, the predominant genre of the checklist, Unnamed Figures wields volume and repetition as a method to account for not simply the profound presence of African Americans in the North but moreover, the trials, tribulations, and triumphs that African Americans navigated in the North. Many of the works of art on display, like Hathaway’s painting, were not originally made with such a project in mind. Following the work of scholars Saidiya Hartman and Marisa J. Fuentes (whom the accompanying catalog names as important influences), the curators worked in a speculative mode, noting in the show’s introductory wall text their commitment to “disrupt the original racial politics behind the images, positing agency for the real historical people whose presence is indicated by those depicted.”

This approach unfolded perhaps most clearly in the exhibition’s central room—a large circular space organized under the theme “White Portraits, Black Lives”—which brought together a series of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English and American portraits featuring white sitters accompanied by enslaved Black attendants. In presenting these paintings, which were conceived originally as demonstrations of white wealth and supremacy, the curatorial team used the space of the label to disrupt the racial hierarchies represented on canvas and center the lives of the enslaved. This move was echoed in a cylindrical banner suspended from the ceiling at the room’s center, which was printed with the names of prominent eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Black Americans, as well as the names of individuals whose likenesses appear in the exhibition. Beneath the banner was a fragment of an ornately carved slate headstone for two young siblings named Lonnon and Hagar who lived in eighteenth-century Rhode Island and were enslaved by a man named Christopher Phillips, whose name also appears on the headstone. The stone was spotlit and installed atop a pedestal as if a sculpture, presumably in a move to honor and memorialize the two siblings. On loan from the South County History Center of South Kingstown, Rhode Island, the headstone has been separated from Lonnon and Hagar’s grave; in an accompanying wall text, the curators estimate that the siblings’ resting place was demolished sometime in the mid-twentieth century. I wondered what it meant for this headstone to travel once again, this time to an exhibition in New York, to be surrounded by portraits of white sitters, many of whom were themselves children, appearing with submissive Black pages. I also wondered about the work of the labels in this space that remained, by virtue of scale and material presence, one where image predominated. Can a label, even one written with utmost care, counter the sheer visual impact of imagery so steeped in racism?

Objects in an adjacent room, “Speaking Back,” seemed to do some of this counternarrative work. The curators assembled a wide range of works by early African American artists and writers working in the Northeast, including portraiture by Joshua Johnson, volumes by late eighteenth-century luminaries Phyllis Wheatley and Benjamin Banneker, and salt-glazed stoneware by the successful potter and entrepreneur Thomas W. Commeraw. Most striking amongst this mix of works by well-known figures, then, was the inclusion of needlework embroidered by young Black women. Two of these examples were genealogical samplers, with one stitched by the Connecticut-born Sarah Ann Major Harris and another by an unnamed daughter of the Heuston family of Brunswick, Maine. In both, shimmering silk threads trace family births, deaths, and marriages from the seventeenth century on. These small works function as a powerful counter to the portraits of enslaved sitters in the preceding room, whose visual logic turns upon the rupture of genealogy and kinship bonds.

In large part, Unnamed Figures is an exhibition about the fact that objects like these samplers are so few and far between, that to think about Black life in the early United States means that one must often think in the absence of a neatly outlined record, archive, or family tree. A section of the show devoted to the Hall family of Baltimore might be seen as an attempt to recreate a genealogical sampler of sorts. Working from Francis Guy’s two paintings of Perry Hall Plantation (ca. 1805), which later in the nineteenth century passed into the hands of the descendants of people enslaved by the Halls, the curators along with researchers Gregory Weidman and Elisabeth Mallin combed through census records, family journals, and photographs to retrace the family’s history. Late nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographs of the Hall descendants appear on the wall next to the Perry Hall paintings, offering an important post-abolition narrative that Guy seeks to all but foreclose in his rendering of the enslaved and “unnamed.” Here, following the exhibition’s title, the viewer is prompted to ask when and to whom are figures unnamed—and for whom names (perhaps names forced upon people by enslavers, and perhaps other names they chose to be called) have always been known.

The case study of the Hall family is a powerful moment in a show that largely takes on historical objects, many of which were conceived by white artists with no particular regard for the Black subjects they painted. Indeed, at other times the exhibition risks being overwhelmed by such imagery, especially in sections towards the end that deal with the proliferation of racist stereotypes and caricatures in the nineteenth century. The argument might be made that these objects, which range from the crude “Bobalition” prints made to lampoon possibilities of Black freedom to a toy minstrel diorama, should be included so as to not censor the realities of racism faced by African American people. And yet, in an exhibition rife with imagery about the unnamed and the absent from start to finish, when does it all become too much? It is difficult to do the work of recovery that Unnamed Figures is committed to, and the exhibition team’s serious efforts to engage this must be acknowledged. At the same time, Unnamed Figures opens onto a set of vital questions that anyone developing an exhibition around the speculative histories of Black life and presence must center on: when does image or object make space for this kind of recovery, and when does it not? (And who is to say?) When—such as in the case of Lonnon and Hagar’s headstone—is recovery or return impossible? Where will that leave the viewer, in the space of a museum at the edge of Seneca Village-turned-Central Park, in looking at these objects? And where will it leave the subjects—real, imagined, present, absent—of these works?

Caitlin Meehye Beach

Associate Professor of Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY