- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Omar Ba’s recent exhibition Omar Ba: Political Animals, at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA), updates W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness, which Du Bois restricted to the African American experience in the United States. Du Bois positioned double consciousness as the burden African Americans endure as emissaries of Black culture, while at the same time pledging allegiance to the ideals of being an American in a society ruled by whiteness. Du Bois writes, “It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness . . . one ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two un-reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder” (The Souls of Black Folk, Edited by Brent Hayes Edwards, London: Oxford World’s Classics, 2008). The Senegalese artist Omar Ba (b. 1977), who today splits his time between Dakar and Geneva, offers a globalist take on Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness, as his work expertly navigates cultural and social identities that exist within a multiverse of Blackness, a cacophony of all Black everything, everywhere all at once.

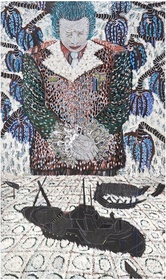

Curated by Leslie Cozzi, curator of Prints, Drawings & Photographs at BMA , Omar Ba: Political Animals is the first solo exhibition at a US museum of the renowned Senegalese-Swiss artist. The exhibition consisted of fifteen large-scale works on canvas and corrugated cardboard, twenty-one works on paper, and three room-sized displays, including a site-specific installation constructed during a one-month residency at the museum. Collectively these works, which feature depictions of monumental figures placed in fantastic environments, global political parties, and abstracted vegetation, situate Black existence across an array of place, nationalities, and genders—all forms not limited to an American or Black Atlantic experience. In the age of globalization, Ba’s work demonstrates, there are multiple interdimensions of being and consciousness. Access to resources such as technology and education, provides the global African diaspora a unique experience of what may be considered a multiverse of Blackness.

Ba deftly presents this globalized approach to the politics of Blackness in his art, depicting the struggle for nation, belonging, freedom, identity, and humanity in a world angled against the fullest expression of melanated consciousness. Recently appointed BMA director Asma Naeem embraces this globalized consciousness and establishes a new direction for the museum, as her decision to house this show demonstrates. “This exhibition reflects the BMA’s vision,” Naeem writes, “to share the work of artists who engage with the African diaspora as part of our broader commitment to expanding the narratives of art history and the artists represented in our galleries” (quoted in Émile Joseph Weeks, “Political Animals: Omar Ba’s American Debut at the BMA Speaks Poetry to Power,” Bmore Art, 2023). A quick view of the museum’s current and upcoming shows, The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century and Recasting Colonialism: Michelle Erickson Ceramics, further demonstrates this commitment by detailing the generational experiences across the African diaspora in music and contemporary art.

Ba’s global perspective can be traced to his upbringing. He comes from a household of two traditionally warring cultures. Ba’s mother is Serer from the village of Tanor Dieng, Guéniène. His father hails from the northern Pulaar-speaking town Nioro. His shared Serer/Pulaar heritage initiates a duality in Ba’s life that reflects the presence of both animism and Islam. His education is further evidence of his global perspective. In 2003 Ba attended Dakar’s l’Ecole Nationale des Beaux-arts de Dakar and, following a chance encounter with a visiting Swiss artist, he enrolled in the l’Ecole Supérieur des Beaux-arts in Geneva in 2005 and, later, at ECAV–MAPS Arts in Public Spheres in 2011. This transnational experience contributes to his recognition and expression of global Black culture in his practice.

Ba champions Blackness through his art by using the color black as a ground, decentering modernist painting’s investment in the white canvas, which also allows his use of color to pop more effectively. The black backgrounds give his monumental figures depth and dimensionality on seemingly infinitely expandable planes. His choice of oil stick, wax pencil, Chinese ink, and porous tip pen to produce enticing reticulating marks, encourages viewers to look closer, delving deeper into the possible meanings of his multilayered canvases. Ba also collages photographic portraits of the people he has met during his travels into his compositions, allowing the everyday African individual a visual visa to virtually travel across institutional boundaries. In doing so Ba’s canvases function as cultural and archival sites for the African diasporic experience.

Ba juxtaposes politics and grief without erasing the contradictions of elected officials who fail to serve the people and instead function to perpetuate a Western system of inequity. His views on Black freedom and Western culpability are evident in works like Le Camp de Thiaroye 3 (2009) where a spectral white figure in military garbs stands at attention on a black background. The image is assaulted by spatters of white paint, giving the appearance of gunshots. The work is a representation of the massacre of three hundred protesting French West African troops by French forces on December 1, 1944. France recognized this crime in 2014, but has yet to apologize. In the colossal Naufrage a Melilla (Shipwreck at Melilla) (2014), a solemn uniformed figure with medals from the International Monetary Fund bows its head with closed eyes in reverence or blind oversight. Below the figure’s bound hands, a tragic tale plays out on a sea of what could be identified as bank notes, while the exposed ribs of a shipwreck represent the thousands of African immigrants who die each year on the North African coast attempting to gain entry to a better life in Europe. Depictions of amorphous African heads of state are present throughout the exhibition, demonstrating the pervasive subjugation of African leaders to Western puppetry.

The installation Not Fiction but Glory (2022), commissioned by the BMA and constructed during his residency in Baltimore, is Ba’s largest work to date. It demonstrates Ba’s commitment to highlighting the African diasporic experience wherever he encounters it. Three hundred fifty-eight cardboard boxes painted black serve as a ground to eradicate the barriers of time and place. Inspired by the Corinthian columns of the White House and the BMA, Ba erects monuments in the memory of abolitionist Harriet Tubman, advocate Frederick Douglass, Senegalese Afrocentrist historian Cheikh Anta Diop, African mathematician Jean Philippe Omotunde, and founder of the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, Patricia Bath, PhD, among others. His depiction of a Senegalese marketplace filled with the limitless potential of the African diaspora frames an alternative universe in opposition to Western-based reality. That alternative space celebrates cultural mixing, the act of giving and receiving, what Léopold Sédar Senghor, poet and first president of Senegal, called “rendez du donner et recevoir” in his promotion of the Negritude movement. Ba’s scintillating examinations of neocolonial power structures and their control of global financial and political systems are tempered through his beautiful depictions of abstracted vegetation, loose feathery brushwork, and use of an enchanting color palette of obsidian black, enameled whites, viridian greens, lapis blues, browns, crimson, and peach. His choice of ordinary materials like corrugated cardboard, whiteout, and painted shoe boxes, along with this use of black ground, offers a firm counter to modernist practices and values.

Ba’s travels have granted him access to a litany of nationalities, cultures, social strata, and class structures and his residency at the BMA allowed him to better eclipse a homogeneous view of Black culture. Expanding beyond Du Bois’s restriction of double-consciousness to an African American experience, Omar Ba grants us access to an experience refracted across cultural borders and encounters, the work itself functioning as a historical artifact of a global Black multiverse. The power of Ba’s work resides in not focusing on one person, one head of state, or one government; instead, Ba shows that Blackness transcends the problems preoccupying individual communities. The current unrest in Senegal is a complicated issue, yet it shares connective tissue with the political situations in Haiti, Palestine, Ukraine, Flint, Michigan, and Baltimore. In Ba’s multiverse, the Western governments and the afterlives of colonialism are all equally implicated and culpable in the complicated politics of the present. It is the viewer’s responsibility to arm themselves with the works of Black critical scholars and artists to expand their vision to include a multifaceted, multidimensional view capable of taming these political animals.

Dominic M. Pearson

MA student, African Diaspora Studies, Art History

University of Maryland, College Park