- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Writing on the decolonial turn in curatorial practice, curator Ivan Muñiz-Reed asks, “How are curators and art institutions positioned within the colonial matrix, and is it possible for them to restructure knowledge and power—to return agency to those who have lost it?” (Afterall, 2020) A possible response to this provocative question is proposed by Reinventing the Américas: Construct. Erase. Repeat.

Organized by Idurre Alonso, this exhibition displays many of the Getty’s collections of European colonial-era engravings, etchings, lithographs, illustrated chronicles, and decorative objects depicting the Americas during the so-called Age of Discovery. The show’s twist is that it seeks to disrupt the biased and stereotyped Eurocentric perspectives pervading these representations, aspects of these images that are rarely unpacked or critiqued when they are displayed in institutional contexts.

The exhibition sprawls across two distinct gallery spaces, separated by a lobby overlooking the GRI’s library below. The first space—comprising three subsections titled “The Allegory of America,” “Wonders of Nature,” and “Narratives of Conquest—is demarcated by moss green walls, perhaps evocative of the virgin forests of the precolonial Americas, and houses numerous vaguely Art Deco, custom-built book display cases. Ample wall texts and object labels, written in both English and Spanish, situate and contextualize the works and the themes of each section.

As Muñiz-Reed points out, revealing the biases of institutions is not always an easy task for Western curators. “It has often been artists—who are better positioned to criticize the institution—working with collections that have perpetrated some of the most interesting examples of epistemic disobedience,” he writes. (Afterall, 2020) Similarly, Alonso has also invited artistic intervention as a mode of dismantling the European conventions and imaginaries perpetuated by these historical representations. In this case, she has solicited the help of the Indigenous Brazilian artist Denilson Baniwa (b. 1984), who contributes artistic interventions aimed at calling into question the underlying assumptions of much of the imagery on view.

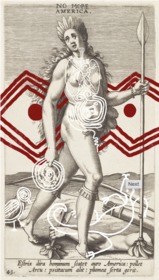

Take for instance a digital print by the artist titled No More America (2022) placed at the exhibition’s entrance. The image is replicated from an engraving titled “Allegory of America,” which appears in Prosopographia, a seventeenth-century Flemish publication propped open in a glass display case nearby. The original plate depicts an awkwardly rendered nude Indigenous woman in a nondescript landscape wearing a headdress and brandishing a spear in one hand with a severed head dangling from the other. At left, a parrot is perched on the ground, and lying at her feet are a severed arm, a bow, and a quiver of arrows, indicating that she has just vanquished a foe. At top, the image is labelled “America,” and below, in Latin, appear the words, “America, the cruel scepter of men, will be seated with gold. A bow: she feeds a parrot: she wears braided feathers.”

Baniwa’s blown-up reproduction depicts the same image but over the engraving’s contours he has added white line drawings of his own: a heart and lungs over the figure’s chest, spirals over her belly, the severed head in her hand, and the nearby parrot, and a lizard outline at her feet. Behind her body, he has added a bold red geometric chevron and dot pattern. He has also changed the title at top from “America” to “No More America,” as a challenge to the image’s original allegorical function from a distinctly Indigenous perspective.

Another type of intervention Baniwa takes is to literally write in pen on the object labels themselves. For instance, on one of the labels for two porcelain female allegorical figures symbolizing the Americas—one white and one Black, both wearing Indigenous costumes and seated astride alligators—Baniwa handwrites the words: “THE REFLECTION IN THE MIRROR IS A PROJECTION OF ONE’S OWN GAZE,” a critical commentary on the historical writing of Indigenous identities in the language of the colonizer.

Baniwa also contributes contemporary video works to the show as a complement to the exhibition’s themes. The title of the entire exhibition is taken in part from his video America: Erase and Repeat (2022), which is projected on a semicircular screen placed above a publications display case. The video documents a ceremonial action the artist undertook dressed as a jaguar shaman, in which he coats Euro coins with black ink, places them on a copied page of a colonial-era publication, and runs them through a printing press, resulting in the images being covered with ink, which according to him represents a reenactment of the erasures of Indigenous cultures by colonizers and “provides the base on which to rewrite a different imaginary about these [Indigenous] territories.”

Another innovative mediation is the inclusion of commentary about the works on view from Getty groundskeeping staff and local community members whose ancestry is rooted in precolonial American cultures. Their observations are presented as texts displayed next to the official wall labels. For instance, located alongside seventeenth- and eighteenth-century engravings titled Fashion and Attire of Mexicans and Indigenous People Working on Cassava, is a text written by Lilia “Liliflor” Ramirez of the Mujeres de Maíz and Sounds of Solidarity groups. It reads: “I remember as a kid looking at illustrations with depictions of Indigenous people in historical books and museums. Back then I had to accept them as a reality, but when I began to learn about my own Indigenous traditions, I started questioning their accuracy. Is this an actual depiction of my ancestors, or is it a somewhat obscured invention? Is this another fantasy by a westerner?”

In another display, the words of a European colonizer are presented via an audio element that accompanies a series of four framed sixteenth-century engravings by the Flemish printmaker Adrian Collaert. These images come from the series, The Discovery of America, which includes a frontispiece depicting a round globe surrounded by Roman gods and goddesses, and three images depicting the explorers Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and Amerigo Vespucci on their respective ships. The prints are displayed in a square grid on the wall, with the audio recording playing an English translation of Columbus’s reports to King Ferdinand of Spain on his first voyage to the islands of Juana and Hispaniola upon his return to Europe in 1493. As we consider the images of these explorers standing proudly on their ships surrounded by mythological sea creatures, we hear Columbus’s own description of the Indigenous people he encountered in these Caribbean islands: “They have no iron, nor steel, nor weapons, nor are they fit for them, because although they are well-made men of commanding stature, they appear extraordinarily timid,” perhaps the very first instance of the primitivist stereotyping of Native Americans that would become pervasive in Europe over the next four hundred years.

The last gallery, decorated in an orange, pink, and black motif, focuses on the theme of nineteenth-century travelers. These included the European artists, explorers, and scientists, who visited the Americas in the nineteenth century to analyze and document the Americas and their peoples. Their images usually emphasized American lands as rich in resources to be exploited, with “new” plant and animal species to be documented, and inhabited by “savage” peoples whose cultures should be ethnographically categorized. This section also spotlights the inaccurate biological theories and scientific racism these images promoted. Of particular note here are the frank and brutal depictions of enslavement, such as a devastating engraving titled The Inhumane Treatment of a Wounded Rebel Negro, by William Blake, from John Gabriel Stedman’s Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam in Guiana (1796), showing a Black man viciously hung from gallows, a small hook piercing his torso, with skulls and bones at his feet, and the ocean and a ship in the distance.

This gallery gives way to the final exhibition space labeled “Denilson Baniwa’s Reinventions,” an area painted black, containing a long glass vitrine and a mural by the artist. The vitrine is a sort of artistic reinterpretation of a cabinet of curiosities, only in this case, Baniwa has curated a collection of fictional ethnographic objects from an invented Indigenous culture that he himself created, including a mask, ceramic vessels, costuming, ritual figures, and maps. Opposite this vitrine appears a colorful line wall drawing intended to evoke Indigenous petroglyphs.

I admit that in past exhibitions of colonial-era publications, I have often found them lackluster and inaccessible because of their dim lighting, and the prints’ small scale, dull black-and-white tones, and their remoteness behind glass displays (books are, after all, meant to be handled). By contrast, this exhibition succeeds in activating and engaging viewers, not only by inviting multiple modes of interaction, but by also foregrounding counternarratives from non-Western and Indigenous peoples—groups rarely invited to comment on art in museums—and presenting them equitably within the exhibition’s display platforms. For these reasons, at least in the case of this sensitive and provocative exhibition, achieving Muñiz-Reed’s call—“to return agency to those who have lost it”—seems possible.

Gillian Sneed

School of Art + Design, San Diego State University