- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

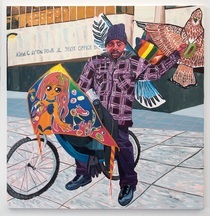

Coming upon Kevin the Kiteman, Jordan Casteel’s big 2016 painting in the galleries of Seattle’s Frye Art Museum, viewers might have been reminded of how the pandemic has utterly transformed urban experience. The piece opened a section of Black Refractions: Highlights from the Studio Museum in Harlem focused on work by former artists-in-residence, the signature studio program of the famed New York institution. As Frye Art Museum curator Amanda Donnan describes in the catalog, the work was the result of a serendipitous encounter between painter and subject. When observing the busy plaza across the street from her studio at the museum, Casteel became fascinated by Kevin’s dedication to flying kites in the midst of all the pedestrian traffic and crowded street life. An artist-in-residence during 2015 and motivated to represent a kind of Black masculinity obscured by mainstream media narratives, Casteel acquired the nickname “painter” when she became a fixture in the neighborhood and painted several portraits of men she encountered in Harlem. Kevin proudly brandishes an array of colorful kites, with the wings of one appearing behind his back as if he were able to fly himself. The specificity Casteel gives to Kevin and the setting—the building name legible over his shoulder memorializes Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the first Black Congressman from the state of New York who represented Harlem from 1945 to 1971—grounds the work in the historical reality of this community and its centrality to Black identity. Given that it was the product of her residency at the museum, Casteel’s painting perfectly reflects the goals of the institution as described by director and chief curator Thelma Golden in her insightful catalog interview with scholar Kellie Jones: the “founders put the mission in the name. Studio. Museum. Harlem. Literally, that’s it” (27).

Curated by Connie H. Choi, associate curator of the permanent collection at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and organized by Golden in partnership with the American Federation of the Arts, Black Refractions provides a sketch of the institution’s history as well as a snapshot of the concerns of Black artists from the museum’s founding in 1968 to the present day. Given recent discussions of how museums should meet the challenges of systemic racism and the intellectual, political, and economic roots of collecting institutions in the history of white supremacy, the Studio Museum in Harlem provides one model of a successful, community-centered, artist-oriented organization that was born out of a similar moment of social crisis and cultural change. The exhibition was organized to circulate a portion of the 2,500-piece collection of works by over seven hundred artists while the museum gets an eagerly anticipated new building designed by Sir David Adjaye at its West 125th Street space.

Among gems by twentieth-century modernists such as Charles Alston, Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Norman Lewis, and James VanDerZee, located in the “Founders” and “Their Own Harlems” sections, the show also offered a chance to see the early work of some of the most noted artists working today. Mark Bradford, Kerry James Marshall, Julie Mehretu, Wangechi Mutu, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, and Kehinde Wiley all had work in the exhibition, but as Choi notes in the catalog, the show is not a replica of a long-standing arrangement of the collection because the museum has never had the space to show these works together. The ninety-one pieces in the Seattle show were divided into six sections: “Founders,” “Abstraction,” “Framing Blackness,” “Artist-in-Residence Program,” “F-Shows,” and “Their Own Harlems.”

Of the two checklists that Choi provided to host institutions, one thematic and one that followed the history of the museum, Frye curator Donnan chose the more chronological organization and added the “Abstraction” section. This grouped together bold paintings from the 1960s and 1970s by artists such as Frank Bowling, Sam Gilliam, Alvin Loving, and Jack Whitten in a single gallery adjacent to “Founders” and effectively foregrounded the era’s debate over nonrepresentational art versus figuration as it pertained to the moral responsibility of the Black artist to effectively “represent” their race.

There were individual works in the show that have featured prominently in the Studio Museum in the past, most notably Glenn Ligon’s Give Us a Poem (2007), originally in the Harlem museum’s lobby. Nicely placed in the Frye to introduce the exhibition and to suggest the occupation of the Seattle museum’s space by another institution, Ligon’s white-on-black, neon light work spells out the word “ME” above a “WE” mounted directly below it and mirroring its form as if reflected. “Me, we” was boxer and activist Muhammad Ali’s response to the artwork’s eponymous request, issued by the crowd assembled for his 1975 appearance at Harvard University. At the Frye, Ligon’s work hung alone at the beginning of the show against a deep purple-blue wall (the same color as the attractive catalog cover by Rizzoli Electra) and served as a powerful entry into the discourse of positionality. During this momentous past year, as the show was hosted by smaller-scale institutions across the country that primarily serve their own regions, the question of who is the “me” and who is the “we” when coming into a space to look at works of art by artists of color has never been more important. The two pronouns alternately blink on and off in Ligon’s work, cueing viewers to consider the dynamics of inclusivity and exclusivity throughout the exhibition.

Another work using electric light was visible down a corridor when first encountering Ligon’s piece at the Frye exhibition entrance, Tom Lloyd’s Moussakoo from 1968. This work was included in the inaugural exhibition of the Studio Museum, a solo show of Lloyd’s electronically programmed light sculptures called Electronic Refractions II (1968). Black Refractions is clearly meant to echo the title of this historically significant exhibition for the institution. With its minimalist design and industrial materials arranged in interlocking diamonds, Moussakoo signals the history of the museum’s commitment to radical art practice at a time when some critics questioned the politics of such work. Lloyd spoke to this issue in a 1969 symposium, declaring that art “can be anything. It can be a painting of a little Black child or a laser beam running around the room” (130).

The historical context for understanding works such as this is nicely explored in the catalog with brief authored artwork entries and with thorough essays by Choi and Golden on the history of the collection and the museum. The author of the entry on Moussakoo, however, mistakenly dates the 1965 Watts Rebellion to the year of Lloyd’s piece and, to my mind, forces a connection between Lloyd’s stoplight-like medium and the history of police brutality during traffic stops.

The historical counterpoint to work such as Lloyd’s is the portraiture of Barkley L. Hendricks, whose 1969 Lawdy Mama was featured in the “Framing Blackness” section of the exhibition and adorns the cover of the catalog. A powerful picture of the artist’s young cousin with a large, “natural” hairstyle surrounding her head like a halo, the work features an arched frame and gold-leafed background that bring the symbols of late-1960s Black style into conversation with medieval religious icons and suggest the lack of images of the Black figure in the history of Western art. A newer generation of artists with work in this show, such as Casteel, Whitfield Lovell, Kalup Linzy, Jennifer Packer, Mickalene Thomas, and Kehinde Wiley, clearly continues Hendricks’s tradition and builds on it.

One of my favorite works in the exhibition, placed near classic photographic pieces by Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems in the “Framing Blackness” gallery, was Steffani Jemison’s Maniac Chase, a hypnotic digital video from 2008–9 partly inspired by early film history. Jemison addresses the history of media representations of Blackness by filming a series of Black male and female figures running through different urban landscapes—an alleyway with a clanging gate, a grassy hill in front of an institutional building, alongside a graffitied wall—and looping them to emphasize the futility of escape from an unseen pursuer. Dressed in the same uniform of white shirt and black pants, the figures become symbolic of any number of urban youths pictured in television and movie chase sequences, but by substituting ambient noise for frantic soundtrack music, Jemison provides the space for reflection on the power and ubiquity of these images in popular culture and their links to the politics of “law and order.”

Black Refractions is an important show that serves to mark a new moment not only for the Studio Museum in Harlem, as it awaits its new building, but also for art institutions in general in the wake of growing popular awareness of the intersections of power, money, and race in the cultural sphere. The final stop for this traveling show was excellently staged at the Frye Museum in Seattle and, as it must have done in other communities during its run, it asked viewers to consider how their own experiences may be “refracted” by the questions the artists pose in this rich and historic museum collection.

Ken D. Allan

Associate Professor of Art History, Seattle University