- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana was a richly textured exhibition on the gender-specific effects of incarceration on cisgender and trans women in the state. The show was centered around a group of over thirty currently and formerly incarcerated women whose life stories formed the basis of visual artworks and music created by a diverse group of artists based in and beyond Louisiana. The works in the show ranged in style and included sculpture, painting, video, installation, photography, and original music played throughout the galleries. Participating artists were selected by museum staff and community stakeholders. The Newcomb Art Museum collaborated with Syrita Steib-Martin and Dolfinette Martin—two formerly incarcerated women who run Operation Restoration, a project that assists women in New Orleans with reentry following imprisonment—to organize the exhibition. Martin and Steib-Martin facilitated the participation of “persisters,” the women featured in the exhibition who use this term to underscore their identity as survivors of a violent and unjust carceral system. Each persister chose one of the selected artists with whom they wanted to collaborate on representing their story.

The exhibition paints a picture of New Orleans that diverts dramatically from the marketing calls to “follow your NOLA” through consumption of its unique culture, and points to the fact that, as the exhibition brochure states, Louisiana “incarcerates more of its own population than any other place and until recently was dubbed ‘the incarceration capital of the world.’” The majority of the persisters are Black cis- and transgender women who became involved in the justice system at a young age. Many were nineteen when arrested and share experiences of coming from communities that are regularly targeted by police, and of having families navigating health disparities. Some had incarcerated parents and others have incarcerated children. One persister recounted serving time in prison for collecting abandoned items following Hurricane Katrina, being confronted by police as a “looter.”

Upon entering the museum, the visitor was met with two information kiosks that flanked the entrance to the galleries. These displayed elegantly designed information cards featuring local and national arts, legal, and social justice organizations addressing mass incarceration. The kiosks also included free stickers with graphics designed by Taslim van Hattum and facts such as “80% of women in jail are mothers missing their children.” Other informational graphics by Hattum were displayed throughout the exhibition and alerted the viewer to statistics regarding incarcerated women’s experiences. A selection of books on mass incarceration were also on display at the kiosks and could be read by visitors in chairs in the foyer.

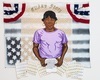

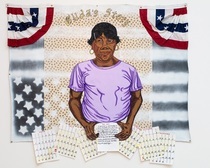

The vibrating blue tones and gold shimmer of The Life Quilt (2018), a large-scale textile work created by the Graduates, a performance collective comprising formerly incarcerated women, welcomed the viewer into the first gallery. The work consists of individual pieces of fabric upon which the names of women serving life sentences in Louisiana are hand sewn and carefully embellished with sequins by Kathy Randels and various members of Mardi Gras Indian tribes. The names are arranged in a repeating grid composition and frame a bust portrait of a smiling Black woman with a halo, resembling the imagery of Byzantine icons. The Life Quilt was juxtaposed with a grouping of portraits of the persisters by Allison Beondé. The framed black-and-white photographs included a mirrored border at the base of each image, upon which a portion of the persister’s oral history was inscribed in black text. The photographs were displayed salon style, adjacent to headphones through which viewers could hear the persisters tell their stories, and tablets were accessible on a bench in the gallery with transcripts of their narratives. Each gallery in the exhibition included audio and textual oral histories and a cluster of persister portraits by Beondé to contextualize the artworks that respond to their particular stories. The use of soft-focus black-and-white photography and the persisters’ intentional poses reflect how, as visual culture scholar Nicole R. Fleetwood observes, imprisoned people use photography “to produce themselves as subjects of value against the carceral state that defines them as otherwise” (“Posing in Prison: Family Photographs, Emotional Labor, and Carceral Intimacy,” Public Culture 27, no. 3, 2015: 492).

The exhibition flowed in a U formation through a series of galleries. A graphic timeline displayed on the floor marked significant dates in the history of prisons in Louisiana and the United States. A cutout of the state of Louisiana was placed on a pedestal in the center of the first gallery, with lights indicating the locations of carceral facilities throughout the state. This gallery included the video work The Arrest (2018), by Kira Akerman, which depicts persister Chasity Hunter sharing the story of her arrest and, specifically, how she was placed in solitary confinement in response to her refusal to accept the condition of incarceration. Her story of resistance resounded powerfully with another work in the gallery, Tammy Mercure’s Wendi (2018), which consists of a series of portraits of Wendi Cooper, a trans woman incarcerated under Louisiana’s Crimes against Nature by Solicitation statute (CANS). CANS specifically criminalizes the solicitation of oral or anal sex for compensation. It carried more stringent punishments than the state’s sex work laws, such as making it mandatory for the individual charged with the crime to be registered as a sex offender. In so doing CANS criminalized the LGBTQ community by outlawing acts that are commonly associated with queer and trans people, one result of which is that a significant percentage of people on Louisiana’s sex offender registry are women and LGBTQ people of color (see Andrea J. Ritchie, “Crimes against Nature: Challenging Criminalization of Queerness and Black Women’s Sexuality,” Loyola Journal of Public Interest Law 14, no. 2, 2013: 355–74). The law was modified in 2011, but only eliminated the sex offender registration for those convicted after August 15, 2011. One striking image in the photographic grouping shows Wendi with her back to the camera, with text from the CANS law written upon her bare skin. This image is paired with a portrait of Wendi looking directly out to the viewer in defiance, refusing the shame the law aimed to inflict on her.

The subsequent gallery was a larger space filled with natural light and several installation works. Notable among these was Amy Elkins’s abstracted digital portraits of faceless, incarcerated mothers posing with their children in a manner reminiscent of traditional family portrait photography. The missing faces and the figures’ stiff poses, based on images Elkins found of models posing in prison uniform catalogs, have a haunting effect when juxtaposed against the backdrop of homey, feminine, Southern-style wallpaper, provoking the question of who has the privilege of being a mother in Louisiana.

The American flag appears in numerous works. It hangs upside down and in black and white behind Keith Duncan’s vivid portrait of persister Gilda Caesar; a black line is struck through it in the ceremonial garment crafted by Cherice Harrison-Nelson, Herreast Harrison, and persister Zina Mitchell; and it is interspersed with images of slave ships and historical images of incarcerated Black people in Epaul Julien’s work. The presence of the flags reflects the exhibition’s critique of the roots of mass incarceration in the very fabric of the United States’ foundations in settler colonialism, slavery, and patriarchy.

While this critique of both past and present was rather subtle and built momentum organically as the viewer moved through the exhibition, the emphasis on the experiences of marginalization that many of the persisters share was somewhat overstated. The brochure text, oral history excerpts in the exhibition, and informational graphics were a repeating chorus of experiences of rape, loss, domestic and institutional violence, and family dissolution. Although there is no question that these stories have a crucial place in the narrative, they at times subsume it. The aim to humanize the persisters through sharing their experiences of oppression at times had the opposite effect, inadvertently creating a flat representation of otherness and victimization that privileges what Native studies scholar Eve Tuck describes as a damage-based approach to addressing injustice ( “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, no. 3, 2009: 416), rather than a desire-based framework that would make the dreams and creative visions of these women central. Several of the artworks in the exhibition, such as L. Kasimu Harris’s reenacted scene of persister Fox Rich reunited with her husband in their bed, resisted the orientation toward damage by featuring the persister’s experiences of love and partnership. Other works that centered African diasporic practices of healing also insisted on the persisters’ complexity and wholeness.

The organizers of Per(Sister): Incarcerated Women of Louisiana aptly describe the project as both an exhibition and a platform. The show is an inspiring example of how a museum can act as a site of social education and transformation when it prioritizes community engagement, responds to local needs, and invests the intellectual, creative, and material resources necessary to produce an exhibition that is both aesthetically innovative and accountable to the community. The strengths of the project lie in its meticulous research; its accessible and attractive exhibition, website, and brochure design that promoted viewer education and engagement; and the leveraging of community and university resources. The years of committed work the Newcomb Museum invested in the project were evident in every aspect of it, and seem remarkable when considering the bureaucracy and politics that attend museum logistics, university work, and any kind of project that involves the prison industrial complex.

Jillian Hernandez

Assistant Professor, Center for Gender, Sexualities, and Women’s Studies Research, University of Florida