- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

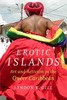

Toward the end of the last chapter of Erotic Islands, Lyndon K. Gill reflects on the benefits and challenges of “queer ethnography” as a methodology. According to the author, situating the speaking subjects of ethnography is necessary in order to both highlight the “experiential specificity” of the ethnographer’s lived time in the field (213) and to avoid turning ethnographic subjects into “representational abstractions” (215) that overlook the internal dynamism and fluid nature of experiences of blackness and queerness across differing geographical and temporal contexts. Through that, the author invites us to work against a certain pattern of ossification and parochialism that has emerged in US black and queer studies, invoking instead black queerness as an “epistemic location in flux,” a “vanishing point of arrival” that opens the way to an interrogation of “the very sedimentation of black queerness that threatens to truncate the black queer studies project” (209). Such an attention to the situatedness of speaking subjects, which the author devotes to both himself and the various other queer subjects whose lives and voices his book mediates, should, I believe, also be extended to my situatedness as a reviewer. I, the reviewer, am a white Portuguese academic working at a British university whose work currently investigates queer sex, its visual representations, and the kinds of epistemologies and ethics we may derive from them. In short, the kinds of epistemologies and ethics at which we may arrive when we come together. Disclaimer: it is from that position—my own—that I approached Lyndon K. Gill’s book.

Erotic Islands is a queer ethnography of the Caribbean islands of Trinidad and Tobago (T&T). Its aim, beyond the aforementioned decentering of black queer studies away from the United States, is to explore the complex ways in which queer subjectivities and eroticism are lived, articulated, and negotiated in a geopolitical context that is too often read as difficult, oppressive, or homophobic, where living a queer life as “we” understand it can look like an impossible task to our North Atlantic eyes, or where queer subjects often risk becoming politically passive subjects of “Western” sympathy, charity, or aid. For, as the author notes at the start of the book’s introduction, “the survival strategies of lesbian and gay Caribbeans are at least as dynamic as the systems of structural and ideological oppression that have attempted to marginalize nonnormative bodies and desires” (1–2).

In order to explore how queerness is articulated and lived in that archipelago nation, Erotic Islands brings together three case studies of artistic and activist practices: Peter Minshall’s designs for carnival masquerades, particularly his work in The Sacred Heart, a carnival show that brought an HIV/AIDS theme to the 2006 T&T carnival parade; Calypso Rose’s gender-bending, same-sex-desiring life and work as a musician, with a focus on her song “Palet”; and the work of the HIV/AIDS community organization Friends for Life, especially its series of grassroots workshops known as “Chatroom.” To connect the three, Gill introduces and develops a particular understanding of the erotic, which he drew from the work of Audre Lorde and then expanded and adjusted with the help of his case studies.

It is that very notion of the erotic that emerges as the book’s main contribution to black (and) queer studies and that, despite its indebtedness to Lorde and the situatedness of Gill’s case studies, the author claims “has the capacity to travel beyond the conceptual locus of its origin” (216). For the erotic in Erotic Islands emerges as both an object of study and a methodological “radiant prism” (11) through which to live and interpret the triangulation of the political, the sensual, and the spiritual in black and queer lives. By broadening the scope of the erotic in such a way—that is, by bringing together political, sensual, and spiritual forms of desire under the domain of a new erotic—one can become more attuned to how “politicized power hierarchies, sensual intimacy, and spiritual metaphysics present interrelated obstacles and opportunities” that queer subjects “must negotiate” not only to survive but also “to clear a space for queer imagining and queer fellowship in their midst” (11). Without this prismatic rethinking of the domain of the erotic, the book argues, it would be difficult to understand the complex ways in which obstacles can also function as opportunities for the development of queer subjectivities and communities, and how queerness, just like blackness, is always already a permanent and situated practice of negotiation and articulation.

In order to argue his thesis, Gill divides Erotic Islands into three major sections, each dedicated to one of the three case studies—the carnival, calypso, and Friends for Life—and each comprising two chapters. The first chapter of each section provides the reader with the historical and cultural background of each case study, preparing one for the case analysis that takes place in the subsequent chapter. Thus, chapter 1 offers a history of the carnival in T&T and is followed by a discussion of Peter Minshall’s The Sacred Heart in chapter two. Chapter 3 introduces the reader to the history of gender play in calypso music, with chapter 4 focusing on Calypso Rose and the dynamics of same-sex desire and masculinity that are played out in her song “Palet.” Finally, chapter 5 takes the reader through a history of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Caribbean before chapter 6 engages with the organization Friends for Life and “Chatroom,” their series of grassroots workshops on sexuality and safer sex, developed as a response to the local challenges presented by HIV. Before each of the three major sections, Gill offers the reader a series of interludes entitled “From Far Afield” in which the author includes a selection of entries from his field journals, in an attempt to weave his own situatedness in the field with the situatedness of the speaking subjects of his ethnography. It is through the book’s formal weaving together of the three case studies, their histories, and Gill’s own diaristic reflections in the field—including various more or less intimate encounters he has had over the course of his fieldwork—that Erotic Islands carries forward its promise of unveiling a new erotic. For, as the book progresses, it becomes increasingly clear how not only each of the three case studies but also the author’s own experience of his time in the Caribbean manifest the three layers of the political, the sensual, and the spiritual that he, after Lorde, proposes as central to any experience of the erotic, to its situatedness, and to its political and ethical potential.

Having said that, one thing that did strike me as missing, or as only tangibly present, was sex itself. I found myself struggling to grasp how a book about the erotic, an ethnography of the erotic, could have nothing to say about actual sexual encounters, about the sexual dynamics of flesh rubbing against flesh, about the queer kinds of embodied knowledge and ethics that can be mediated by flows of desire and the embrace of sexual pleasures—in short, how very little was actually said about Caribbean sexual cultures. For that reason, the project of the book—the erotic it tries to grapple with—felt slightly incomplete in the exact same way that Lorde’s “The Uses of the Erotic,” to which Erotic Islands is so indebted, also feels. Both Lorde and Gill, in their different and yet related attempts to articulate together the political, the sensual, and the erotic, end up circumventing the sexual in the sensual, something that I read in Lorde’s forceful and problematic separation of the erotic from the pornographic, and her subsequent valuing of the former via a devaluing and rejection of the latter.

Despite its deep and very welcome concerns with sensuality and the erotic, with vision, sound, and touch, Erotic Islands still manages to present sex as somewhat of an abstraction—as an absent presence—and therein lies, in my view, its single shortcoming, which has brought to mind some of the concerns Tim Dean raises in “No Sex Please, We’re American” (2015). Identifying a recent pattern of increasing desexualization of US queer studies, Dean writes that “the claim that sex exceeds the personal also risks abstracting eros from embodiment by refocusing attention on social or institutional power relations. . . . Sex may be political, but this fact should not license the wholesale drifting of critical attention from the former to the latter” (American Literary History 27, no. 3: 623). And that leaves me wondering about the extent to which that move away from sex in recent US queer scholarship may go somewhat toward explaining the absence of sex from Lyndon K. Gill’s “erotic,” despite the author’s best efforts to trouble the sedimentation and parochialism he rightly identifies in US queer and black studies.

João Florêncio

Senior Lecturer in History of Modern and Contemporary Art and Visual Culture, University of Exeter, United Kingdom