- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Based on manuscripts in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s collection, the one-room exhibition presented a well-defined overview of medieval ideas and depictions of prejudice and persecution. Even though the title of the exhibition contained the phrase “medieval world,” this was effectively the present-day world of Christians in western and central Europe in the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries. This misnomer in the title does not distract from the nuanced treatment of the exhibition’s illuminated manuscripts, each with carefully chosen examples of themes such as (per the exhibition website Outcasts: Prejudice & Persecution in the Medieval World): ableism and classism, stigma of disease, misogyny, homophobia, Islamophobia, censorship, slavery, whitewashing, tokenism, and anti-Semitism.

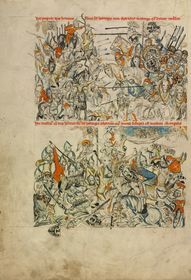

The website’s exhibition resources offer clear explanations of how these themes are depicted, each geared toward the specific image that is described. Thus, two scenes of “The Battle of Liegnitz and Scenes from the Life of St. Hedwig” (1353) show Mongol cavalry fighting savagely and their dead cast into hell. (This scene, perhaps, might deserve an additional label since the Mongol forces of the early thirteenth century, when the event took place, had not yet converted to Islam.) In an initial painted in the circle of Stephan Lochner in the mid-fifteenth century, a white Queen of Sheba kneels before Solomon (ca. 1450) in a typical example of whitewashing, even though—as the label explains in detail—medieval commentators tended to refer to her as black. That both figures are presented in the dress of fifteenth-century European courtiers only adds to this attempt to bring a scene taking place in a distant time and place into a familiar present. Conversely, an Adoration of the Magi by Georges Truber shows Balthasar as a black man, a convention by the time this image was painted in the late fifteenth century. One of the centerpieces of the exhibition, and placed close to the introductory text, is the Stammheim Missal opened to a double page with Christ in Majesty and The Crucifixion. At first sight, the images created in Hildesheim (ca. 1170) do not appear to contain much in the way of the exhibition’s themes. However, the close description in the labels points out how the personification of death in The Crucifixion is closely related to medieval caricatures of Jews, a theme that is also repeated in the figure of Synagoga. Other images disparage or mock the ill, disabled, and poor while others profess misogynistic sentiments by depicting women as sinful. To the curators’ credit, each image is carefully explained within its specific historical context, generally also with detailed references to the text in which it appears, and that often informs what is shown in the image. Each case presents a theme, and the different topics are brought together in introductory text.

Overall, the exhibition was also successful because the small selection of manuscripts shown allows for the close reading of both images and labels that is necessary in order to understand the complexities of the themes represented here (and, hopefully, to begin to reflect on how they relate to contemporary attitudes towards the same questions). A little less successful, in my view, is the presentation of two seventeenth-century manuscripts—one from Peru, the other from an Armenian context in Safavid Iran—that are presented as a nod to areas and periods beyond medieval Europe. While this point is valid and important, the questions seen in these two manuscripts are not quite the same as those discussed in the other objects. Thus, the manuscript from Peru (Ms. Ludwig XIII 16) was created in a Spanish imperial context and opens up questions of colonialism and its representations of locals. The Armenian Bible, with the Safavid silk fragments used on its interior covers, points to cross-cultural artistic practice perhaps more than to the Ottoman-Safavid conflict’s effects on the Armenians of Julfa that are put forward in the label in a way that, in my view, needs further contextualization.

While no catalogue is available, a post on the Getty Research Center’s blog gives a clear overview of the goals that the curators, Kristen Collins and Bryan C. Keene, pursued with this small selection of illustrations and connects it to broader debates about diversity and inclusion in medieval studies. The blog post also demonstrates the curators’ and their institution’s commitment to transparency. It also fosters audience engagement in the curatorial process, in that the post was written before the exhibition was finalized and thus allowed for changes to be made—quite the opposite of the final statements of catalogue essays. Overall, the concepts described in the blog post were successfully addressed in the nuanced exhibition texts, in that issues were carefully explained in ways that do not presume knowledge about medieval notions of “otherness.” There are here several connected conversations. One is related to scholarship on the Middle Ages and how it should address areas of the world beyond Europe, even though this also comes with a discussion of whether terms such as “medieval” and “Middle Ages” apply globally. A further discussion, and this is the one primarily addressed in this exhibition, relates to how categories such as race, gender, religion, and sexuality function in (here primarily European) medieval contexts, and the ways in which we as medievalists today can address them in being mindful of both historical frameworks and contemporary concerns, especially here in the United States. A further question, beyond the scope of both the exhibition and this review, is that of diversity within medieval studies. (Unfortunately, the venom in some of the comments on the blog show just how much resistance such important efforts often meet.) Moreover, while the curators refrain from making connections to present-day politics, one cannot help but notice the timeliness of choosing to comment on medieval attitudes towards those who are placed beyond the confines of very narrow margins of normality: foreigners, Muslims, Jews, women, LGBTQ individuals.

Patricia Blessing

Assistant Professor, Department of Art History, Pomona College