- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

“Klein, aber fein” goes the German saying: small, but excellent. That is how I would describe the exhibition organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art to showcase drawings by Matthias Buchinger (1674–1740) from the collection of Ricky Jay. The phrase could describe Buchinger’s drawings, which are astonishing examples of micrography, a technique whereby minutely drawn words create an image. The practice has a long history, which the exhibition examined, but by any standard Buchinger was an exceptional practitioner of the art. “Klein, aber fein” could also be applied to Buchinger himself, since he was born without legs or hands and stood no more than twenty-nine inches in height. Yet despite obvious physical challenges, his was a life filled with experiences beyond what most people with disabilities imagined for themselves in early modern Europe. Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay brought his story to a broad public and was a good example of how a small but carefully crafted exhibition could reveal, instruct, and delight its audiences.

Ricky Jay is a talented conjurer, particularly so in sleight of hand, where he has few equals. He is also a historian who has written several books on the history of magic, card tricks, curiosities, and what might be called the visual culture of bizarre entertainments. It was in historical mode that Jay first encountered Buchinger, who made his living as a traveling performer three hundred years ago. Hailing from Ansbach, Germany, Buchinger performed shows that demonstrated not only that he could do things unexpected of someone born without hands (load a gun, shave himself, do card tricks, play musical instruments) but also that he did these things more skillfully than many people born with hands. His talents took him across Germany to Denmark, France, Britain, and Ireland. It was in the British Isles that he spent his life after 1717 and enjoyed his greatest renown, with the English press christening him “The Greatest German Living.” The exhibition culminated the more than thirty years of research that Jay has devoted to Buchinger. Several drawings displayed were from Jay’s personal collection—a few are now promised gifts—and he is as informed about Buchinger’s activities as anyone alive today.

The exhibition was installed on the museum’s second floor in the galleries just outside the Prints and Drawings Study Room. These comprise little more than a hallway leading off of the Grand Staircase. There are obvious disadvantages to the space, not least its loud, bustling atmosphere and the awkward location of doorways. But in this instance the setting worked in the exhibition’s favor, since it brought large numbers of visitors into direct contact with Buchinger’s art. Many likely did not come to the Met specifically to look at this exhibition, but once there, they lingered. Entering the space from the staircase, they first encountered drawings by Buchinger as well as images made to advertise his performances. To get a sense of what it is like to look at a Buchinger drawing, one should imagine a common 5″ × 8″ index card. Most of them are approximately that size, and none are larger than a piece of notebook paper. His portrait of Queen Anne of England (1718), for example, was drawn in ink on a sheet of vellum measuring 5 1/4″ × 7 1/4". It represents an oval roundel likeness of the monarch modeled after officially circulated images and containing an elaborate border frame consisting of three laudatory texts. Around those are more purely fanciful ornamental leaves, curlicues, flowers, and other decorative shapes. It is only when one observes the drawing at very close range—no farther away than a few inches—or uses a magnifying glass (which the Met helpfully provided) that one realizes that parts of Anne’s dress and all of her hair are made up of tiny words, in this instance the text of the Old Testament Book of Kings. Then, upon further observation, it becomes apparent that parts of the ornament are likewise made up of words, which loop over themselves in intricate twists and turns rendered nearly perfectly symmetrically. And while one marvels at the presence of writing in this image’s fabric, the incredible detail of the drawing’s components also becomes apparent. Anne’s royal gown includes an intricately rendered depiction of St. George and the Dragon on the bodice, drawn with such precision that the individual teeth in the dragon’s mouth are visible. The amount of visual information presented in this drawing is truly stunning. As a feat of mechanics alone it would be an immense achievement for any artist, let alone one with short arms and no hands or fingers.

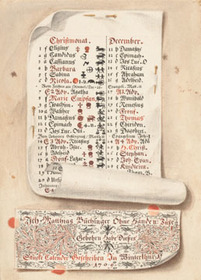

The exhibition displayed several similar drawings by Buchinger, which Jay speculates may have been prepared in advance of his shows. There is little record of exactly how he made them. It is possible, Jay suggests, that Buchinger used optical devices in private and then finished them in front of his audience, thereby generating a sale. Buchinger drew portraits, family trees, renderings of biblical texts, and calendar pages. He signed many of these with a statement similar to that found on the Queen Anne drawing: “This is drawn and written by me Matthew Buchinger, born June 3, 1674, without hands & feet in Anspack in Germany.”

It would be hard to deny that an element of astonishment permeated the gallery as viewers looked at Buchinger’s works. The posted security guard found himself pressed into discussions with museumgoers, many bowled over by the drawings’ technique and eager to convey their amazement to the nearest museum representative. In that sense, the Met’s visitors looked at these images in more or less the same way that audiences did three hundred years ago: as perplexing and impressive examples of technique by someone who, in appearance, would seem to lack the necessary physical requirements to make them. But to the Met’s credit, the exhibition attempted to convey a broader art-historical point, namely that there is a long history of texts being used to create images and that Buchinger’s efforts are one example from a much bigger practice. Interestingly, the exhibition’s curators downplayed the theme of disability and art. One wall section displayed prints of other famous performers with disabilities, and one could imagine Buchinger’s works contextualized as part of a narrative about disabled individuals as art makers. But that was not the primary framework here. Instead, Buchinger’s drawings hung alongside a selection of works on paper, spanning many centuries, which combined words and images in surprising ways.

The closest parallel to Buchinger’s technique is Hebrew micrography, a Jewish calligraphic tradition in which minutely drawn letters are used to create ornamental designs. The Met included several examples of this in the form of impressively illustrated Hebrew scriptural books. But those were just the beginning. Another dimension of this history was displayed in the form of decorated initials from printed books. Many, in an inversion of Buchinger’s practice, used abstract ornamental forms to decorate clearly delineated letters. The exhibition included examples from well-known printmakers like Bernard Picart and Martin Engelbrecht, as well as a particularly beautiful Roman alphabet with antique architectural backgrounds done by the eighteenth-century Bolognese artist Pio Panfili. Another context for Buchinger’s art was the history of penmanship and writing manuals. The show included several examples of such texts alongside sheets illustrating virtuoso penmanship, and it continued into twentieth-century experiments with imagistic wordplay. Several were Futurist prints, including by Filippo Marinetti and Raoul Hausmann; among recent U.S. artists, Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns were obvious points of reference. Twombly made a particularly stimulating juxtaposition with Buchinger, as his abstracted graffiti-like calligraphic images emerged as modern, perhaps jaded, versions of Buchinger’s figural and textual proficiency. The exhibition took the word/image connection into contemporary art with examples from the oeuvres of Jacob El Hanani, Suzanne McClelland, Tony Fitzpatrick, and Glenn Ligon, each of which in different ways plays with how words can construct an image.

The result was an intriguing show, one that managed at once to illuminate the life of a little-known historical figure, to examine a historically significant art form, and to suggest the ways in which the exhibition’s central works of art connected with broader artistic practices. Jay authored a book—Matthias Buchinger: “The Greatest German Living” —to accompany the exhibition. Including many full-color reproductions of Buchinger’s drawings and related images, it is less an exhibition catalogue than an investigation of Buchinger’s life as seen through the lens of a devoted collector. Jay himself is as much the book’s subject as Buchinger, and for those who find interesting the ways in which collectors acquire their objects, it will make appealing reading. Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay demonstrated that when it comes to certain works of art, less is indeed more, since the smaller, more focused structure of this exhibition yielded greater insights than many much larger shows.

Michael Yonan

Associate Professor, Department of Art History and Archaeology, University of Missouri