- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Mexico City-based Belgian artist Francis Alÿs has long been interested in socio-political issues stemming from territory and displacement within marginalized communities, as witnessed through the vestiges of immigration, natural disasters, and warfare. Thus, it is no surprise that these themes feature prominently in three projects in his major solo exhibition, A Story of Negotiation, curated by Cuauhtémoc Medina and beautifully displayed at the Museo Tamayo. Installed in three generously sized white-cube spaces, Don’t Cross the Bridge Before You Get to the River (2008), Tornado (2000–2010), and Reel-Unreel (2011) consist of a symbiotic relationship between the artist’s chosen mediums of film and painting. Alÿs’s socially engaged art practice and dialogic negotiations with minority groups lead him to embark on journeys through various cities, captured on film.

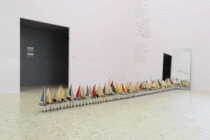

In Don’t Cross the Bridge Before You Get to the River, Alÿs lined up toy sailboats in a single line along the floor to face a mirror mounted on a wall. Providing the illusion of many more boats and an infinite horizon, these same toy boats appear in the accompanying film installation, in which a group of children position them to cross the Strait of Gibraltar. In an attempt to symbolically unite two countries scarred by contested border crossings, the innocent gesture of sailing boats across the water functions as a metaphor for a bridge. (The work is the next chapter in Alÿs’s Bridge / Puente project from 2006, in which the artist also used toy fishing boats to simulate a bridge crossing, this time between Cuba and Florida.) While not endeavoring to solve immigration problems through any overt action, the metaphor offers a benign cultural and political exchange. The captains of the ships, so to speak, are local youth that the artist hailed from the geographic locations for this particular work: Gibraltar, a British overseas territory on the southern coast of Spain, across the strait from Morocco. The strait is just over eight miles wide at its narrowest crossing, and it has become an infamous zone for illegal border crossings from Africa, particularly Morocco, into Europe. The water is known to be particularly dangerous, and many migrants have lost their lives. About this work, Alÿs has stated, “the Strait seemed like the obvious place to illustrate this contradiction of our times: How can one promote global economy and at the same time limit the global flow of people across continents?” (“Francis Alÿs: Gibraltar Focus, June 29–September 8, 2013, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo,” e-flux: http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/francis-alys-2/).

This contradiction is made apparent as viewers watch the children’s resolute and hopeful march into the crystal blue water, gripping the tiny colorful boats and then releasing them, like kites or helium balloons, into a summer sky: one is filled by an impending sense of doom and vulnerability as it appears as though their fate is sealed, with little to no control. The boats in their bid to stretch across the strait are an important symbol of the bridge to which Alÿs’s title alludes, but which will, in fact, never make it to the other side. When one considers the death of innocent children within this equation, it becomes all the more tragic, particularly in light of current events, such as the three-year-old Syrian boy, Aylan Kurdi, who received much media attention in August 2015 when a soldier discovered his body washed up on sandy shores in a small town in Turkey after an unsuccessful flight attempt by his family.

With Tornado, Alÿs directs his attention closer to home. It was created over the course of a decade, when in 2000 Alÿs began to visit the Mexican countryside to document, on camera, footage of the turbulent and forceful motions of tornados as they violently whipped from one field to another. His literal and embodied eye of the storm has been captured in multiple shots, and obviously becomes another metaphor for the political disruption and social chaos in Alÿs’s adopted country. At several stages of the calamity, where Alÿs is temporarily blinded by the dust that swirls around him, calmness and quietness descend on the landscape for a moment or two, offering a quick pause for reflection and even for escape from the madness. To emphasize what it takes to survive within these precarious conditions, Alÿs has set up a series of diagrams and drawings that explore various states of mind provoked during moments of disorder and building on the momentum of upheaval. The drawings are colorful and abstract, but two, in particular, are separately labeled “explosion” and “implosion” directly on the paper by the artist’s hand, and each show a large orange, red, and yellow circular beam radiating dangerous 360-degree flashes around their circumferences. While this suggestion of an interiority and exteriority references the havoc wreaked on both mind and body as witness to the tornado, these explosive illustrations might also visually imitate the “bang, bang” sound effect of a gun once the trigger is pulled, or the process of bullet shrapnel disintegrating. Certainly a culture of guns is one that permeates the sinister elements of Mexican society.

These associations with other forms of violence are more explicit in light of the juxtaposition established by Alÿs and Medina. Upon entering the third and final installation, danger becomes prominent, as viewers are greeted by another circular display, this time of hand-crafted guns propped up on the floor. It is only after viewing the accompanying film that one may register that the barrels of bullets in the sculpted guns have been replaced by film reels, a move that links to the installation’s overall concept. Reel-Unreel was produced during Alÿs’s residency in Afghanistan in 2011. The film’s most powerful signifier comes in the form of a simple old-fashioned film reel, which is wildly unraveled when it is enthusiastically rolled along the dusty rubble of Afghan streets by the artist’s familiar choice of protagonists, children. They use the reel as a makeshift toy in a game that involves passing through a trouble-ridden landscape as if in a momentary state of freedom or escape from the turmoil around them. Alÿs’s vision is once again revealed in his clever deployment of metaphor, where the very reel that is literally “unreeled” or “undone” by the children becomes a protest action of sorts regarding local disapproval of how Afghans are frequently narrowly portrayed by Western media. The children’s engagement with the film reel also nods to the real-life circumstance of the accidental destruction of film reels during military conflicts in Kabul.

Film reels are not the only casualty of war in this place, but Alÿs’s poetic gesture, with the aid of objects infused with new meaning, is powerful enough for the message to become resonant. Small sculptures, paintings, drawings, and handmade animation loops accompany the film installation. Most noticeable is Alÿs’s regular use of color bars resembling TV test patterns strategically painted over people and landscapes. The artist has spoken about how he used this feature to distance himself from the memory or translation of his experience, and also as a means to convey his realization regarding the impossibility of ever truly capturing an accurate representation of his time there (Barbara A. MacAdam, “Francis Alÿs: Architect of the Absurd,” ArtNews [July 15, 2013]: http://www.artnews.com/2013/07/15/architect-of-the-absurd/).

Alÿs spends concentrated effort focusing on the complexities of each of his projects, and Medina is equally committed to ensuring that visitors take away an in-depth experience of the artist’s process, execution, and outcomes. What is especially critical and enjoyable about this presentation is the realization that, while Alÿs is developing a reflexive pictorial language based on his engagement with these embattled communities, both he and Medina insist that all these objects, as byproducts of the exhibition, become another form of action in and of themselves. The political objecthood of the exhibition is woven into both the narrative and orientation of the show as it unfolds from beginning to end in three chapters. What can be seen in these objects is the same message Alÿs performs in his films. Similar to past presentations of the artist’s work, such as Francis Alÿs: A Story of Deception (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2011), there are subtle and alternating repetitions of the same idea, demonstrated by installations that are contextualized by the thoughtful presentation of the “props” used to support the production of the works.

Alÿs’s stories of negotiation, despite their chapter-like presentations and the overarching curatorial navigation, never actually finish. The artist’s unique interpretation and reinterpretation of historical events is a cyclical journey, given his topical themes. The opportunity to reflect on the important ideas radiating from the objects in juxtaposition with the artist’s films made this exhibition particularly memorable.

Amanda Cachia

PhD candidate, Department of Visual Arts, University of California San Diego