- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

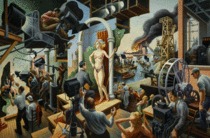

Touted in museum press releases as the “first major exhibition in more than twenty-five years to feature the life and works of the renowned American painter Thomas Hart Benton,” American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood explores the complex intersections between the work of one of the United States’ most revered Regionalists and the American feature film industry. In its staging at Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art (the third stop on a four-city tour), American Epics includes some of Benton’s best-known works, such as People of Chilmark (1922) and his mural-form explorations of the colonization, settlement, and industrial urbanization of the North American continent (1920–28), along with less familiar paintings that engage explicitly with American cinema. Among the latter, Hollywood (1937)—an expansive pictorial summary of the making of a big-budget studio film—and a selection of paintings, drawings, and sketches that provided the bases for movie posters and promotional brochures for film versions of The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Long Voyage Home (1940), and The Kentuckian (1955) offer the keenest insights into Benton’s work for and about the silver screen. Curated by Austen Barron Bailly of the Peabody Essex Museum (where the show debuted) along with Margaret C. Conrads, formerly of the Amon Carter, and independent curator Jake Milgram Wien, American Epics situates Benton’s artistic practice within the trajectories of two venerable traditions: the literary epic and the cinematic blockbuster.

The exhibition is well placed in terms of chronological relationships to works in the Amon Carter’s permanent collection: en route to the galleries, visitors pass an assortment of paintings, graphic works, and sculpture that predate and provide a broader contextualization for Benton’s oeuvre, conditioning the viewing experience through a subtle sense of aesthetic preparation and logical anticipation of the forms, figures, and subject matter that constitute American Epics. Projected movie-title-style text and dramatic typeface announce the exhibition, and a self-portrait of Benton, shirtless and very closely resembling the handsome, swashbuckling movie idol Douglas Fairbanks, is prominently placed to welcome to viewer. To one degree or another the works in American Epics connect through the cinematic, whether in terms of scale, composition, or explicit visual reference. Through this lens, the dozens of paintings that follow reinforce, complicate, and enrich Benton’s place in the canon of American painting. The exhibition encompasses multiple sections that comprise well-known works, paintings related specifically to film, work related to great American literature, and a series called The Year of Peril (1941–42), which casts a completely new light (or perhaps a completely new shadow) on Benton’s oeuvre. In these galleries we see Benton at his best, with such canvases as King Phillip (1922), with its sinuous body, heroic nudity, and pensive mood, and at his very worst, with the horrifying racism, xenophobia, and jingoism of the imagined rape scene of Invasion and a dying Japanese man caricatured to the point of deformity in Exterminate! (both painted in 1942).

Parallel to the undercurrent of the cinematic that binds together the exhibition’s images, objects, and time-based work, three corollary issues emerge: various forms of exposure, the complexities of visual appeal, and a multitude of unresolved (or perhaps unresolvable) tensions. For example, Benton’s exposed bodies, some laboring willingly and some in subjugation, give way to visual accounts of the Native American genocide and the brutalities of slavery—and in the process expose the harsh realities that underpin the American project. Though not necessarily intentional on Benton’s part, these representations take on the appearance of iconic film stills when considered within the context of the exhibition. These descriptions intermingle with interrogations of race and racisms, the pathologies and mythologies of Manifest Destiny, and constructions of white masculinity in urban and rural American milieus. Benton’s paintings both celebrate and call into question the visual appeal of the epic and the heroic as they apply to destinies and masculinities, while at the same time exploring stereotypes, caricatures, and archetypes in expressions familiar but in no way comforting. The pictorial expression of unresolved tension appears with acute potency in Benton’s Negro Soldier (1942) with its man on the front lines risking his life to defend a country that considers him a second-class citizen. This image, too, could qualify as a film still, but Benton’s portrayal veers more toward demeaning than heroizing, retaining just enough nobility to register the inherent contradictions of racialized identity. As the exhibition unfolds, it becomes increasingly clear that Benton had a “cinematic sense” as a painter—not only in terms of the scale of his works, but in terms of process; and as the ephemera included in the galleries demonstrate, Benton story-boarded his paintings in a method comparable to the preparation of a film shoot. His time spent on film sets in the first half of the twentieth century shows up in drawings, sketches, and cartoons depicting every aspect of filmmaking from set design, sound dubbing, and editing to studies of camera equipment and spotlights. The influence is also apparent in Benton’s painstaking planning and staging of his murals and his individual canvases.

Indeed, most of Benton’s larger-than-life canvases, with their figures’ twisting monumentality crafted through lustrous, muscular brushwork, create the same effect and affect one might have experienced in a movie theater in the days when films were still made on huge, purpose-built stage sets. The tactile richness of that brushwork becomes especially apparent when experienced in close proximity to the deadening surface of to-scale digital reproductions included in the exhibition. (The substitution of digital prints for paintings has appeared with alarming frequency of late and always works against both artist and curator; one hopes that this instance will be one of the last.) In a similar vein, the scale of Benton’s paintings is cast into sharp relief by the intermittent placement of flat-panel monitors a fraction of the size of nearby canvases. This tactic creates a tension born of inversion. Scenes from black-and-white film classics intended to be seen on enormous screens and heard and felt through powerful sound systems in a movie palace are here reduced to low-resolution pixels with tinny dialogue and thinned soundtracks emanating from electronic speakers. The multitude of these monitors, all displaying different content and playing simultaneously, creates an unfortunate and distracting din. The distraction is intensified by the architectural limitations of the Amon Carter gallery spaces in which the paintings and monitors are mounted: there simply is not enough room to accommodate and thus realize the exhibition’s original ambitions. Grand-scale paintings require a certain viewing distance in order that one might fully appreciate their compositional force; in the rare instances in which one might achieve such distance in American Epics, other gallery walls partially obstruct the view.

The images in the impressive catalogue that accompanies the exhibition sometimes fare better than those in the galleries, with reproductions in the book being of substantially higher quality than the digital prints on the walls. A range of thoughtful, rigorous, and entertaining essays and case-study analyses by curators, art historians, specialists in area studies, and by Benton himself helps to contextualize his work. Erika Doss’s essay, “Mining the Dream Factory: Thomas Hart Benton, American Artists, and the Rise of the Movie Industry,” which juxtaposes Benton’s film-subject paintings with those of fellow artists Reginald Marsh, Stanton MacDonald-Wright, and Edward Hopper, deftly examines the extent to which American painters engaged with the American film industry. Pellom McDaniels III’s exacting analysis of the black male body makes for especially stimulating and revealing reading. Scholarly, thought-provoking, and at the same time accessible, the catalogue recommends itself to readers of all levels from expert to novice.

Despite the challenges presented by the spatial realities of the galleries, the exhibition succeeds on the strength and originality of its curatorial vision and on the surprises and provocations that promise to inspire a resurgence in Benton scholarship. The paintings’ themes, in their myriad discrete and combined forms, signal, above all, Benton’s ability to convey, with distinctive aesthetic potency, the sense of unambivalent ambiguity that seems so central to American self-perception then as now. Benton’s feelings are strong and vigorously expressed, but at the same time he seems unable to fully reconcile himself to the sometimes violent and too-often hypocritical notions that inform American identities. Through its interrogations of race, gender, militarism, propaganda, and media-induced illusions of what it means to be an inhabitant of the United States, American Epics resonates with a peculiar urgency in a twenty-first-century America rife with internal divisions.

Stephen Caffey

Instructional Assistant Professor of Art and Architectural History and Theory, Departments of Architecture and Visualization, Texas A&M University