- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

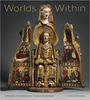

In Worlds Within: Opening the Medieval Shrine Madonna, a group of about forty sculptures known as Shrine Madonnas are the device for Elina Gertsman’s ambitious exploration of late medieval devotion. Also known as Vierges ouvrantes, most Shrine Madonnas are carved from wood and dated to between 1270 and 1500. Some are small enough to fit in a person’s hands, while others are almost life size. All depict the Virgin Mary seated on a throne and holding the Christ child. The exterior opens up to reveal an interior cavity, which usually houses a sculpted Trinity and is decorated with painted or sculpted scenes of the life of Christ. These sculptures are now in parish churches and monasteries across Europe, as well as in private and public collections in both Europe and the United States.

Past studies of these and other kinds of late medieval devotional objects have tended to focus on establishing regional styles through a comparative formal analysis. Gertsman instead aims to suggest ways that late medieval audiences understood and responded to these objects. Gertsman investigates the performative, ludic, sensual, and somatic aspects of devotion through four primary lenses, or “modes of viewing”: vision, the body, performance, and memory. These modes knit together the wider social, cultural, and devotional contexts, not only of these “culturally charged prismatic object[s]” (9), but of late medieval Europe more broadly. Gertsman’s approach is broad in every sense: her source material, both visual and textual, is interdisciplinary and pan-European, the result of the author’s travels across the Continent and into Scandinavia.

Chapter 1, “Secrets: Revealing Bodies, Fragmented Vision,” engages medieval theories of vision to better understand a wide array of related late medieval devotional objects that enclose and reveal their interiors. These objects—including reliquary cabinets, paneled altarpieces, sepulchers, and sculpted shrines—present a series of binary oppositions: closed/open, inside/out, etc., and Gertsman argues that it is through this act of opening and closing (what she terms as “generative fragmentation”; 19) that these objects create meaning. Gertsman posits that these sculptures engage the dynamics of liminality, presenting the Virgin’s permeable body as a border that can be crossed on the path to salvation. Citing the changing concepts of vision—from extramission (the belief that the eye emits rays of light that penetrate the object being viewed) to intromission (the belief that the object itself emits an image that is imprinted upon the interior of the eye)—as well as the shift from materiality to visuality in thirteenth-century art, Gertsman argues that the Shrine Madonnas, and other objects that open and close, reflect the late medieval privileging of the visual and tactile availability of the sacred. The act of opening and closing also reconciles “two seemingly incommensurable spaces: the finite body of the Virgin and the infinite world within her womb” (48). The Virgin’s body thus becomes a place for a sort of holy alchemy, a tabernacle where the miracle of transubstantiation can occur.

Chapter 2, “Ruptures: Holy Anatomy, Affective Obstetrics,” presents medieval approaches to the female body and the contradictions inherent in Mary’s sacred anatomy. Using a Rhenish Madonna now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a case study, Gertsman explores the medieval understanding of the womb as a multi-chambered organ and points to parallels with the ways in which multiple scenes are arranged on the interiors of shrines’ doors. She connects the seam that runs down the length of the shrine to the incision made during a caesarian birth or during dissection, which was increasingly tolerated during this time. She sees the “rupture” of opening the shrine as a “visually brutal” act, which “problematizes the painlessness of the Virgin birth and the inviolable wholeness of Mary’s body” (77). To reconcile this difference, Gertsman argues that “it is imperative to consider the Shrine Madonna within the discourse of monstrosity that shaped perceptions of the divine in the later Middle Ages” (81–82). She points to the displaced breast in Shrine Madonnas that double as images of the nursing Virgin, or Virgo lactans, as evidence of Mary’s monstrosity, but I would caution against reading such displacement with a negative connotation. Instead, the displacement of the breast—which draws the viewer’s attention, as Gertsman later notes—serves as a way to set Mary apart from all other women. Mary’s special status is borne out by the many medieval plays that Gertsman cites, which wipe away any anxiety surrounding Mary’s pregnancy by insisting upon the cleanliness of Christ’s delivery and the intact nature of Mary’s body postpartum.

Chapter 3, “Play: Animate Substance, Uncanny Performance,” explores the performative aspects of these sculptures and of late medieval devotion, including Passion plays. Gertsman presents two case studies: the first explores a Shrine Madonna (now in a fragmentary state) within the context of a medieval parish church of the Church of the Holy Cross in Hattula, Finland, and its mural decoration of Marian miracle stories. The second, a Shrine Madonna from Yvonand, Switzerland (stolen in 1978), considers the ways in which the sculptures might be thought of as animated. As the shrine’s doors parted, Mary’s arms opened in a gesture of welcome. Additionally, the Christ child could be removed completely, meaning that Mary could be activated independently from her son. Although Gertsman includes in her discussion a range of sculptures that could be manipulated, whether by gears or by hand, she argues that statues did not need to have moveable parts to be thought of as moving. The performing body was thus unstable, allowing for a slippage between what was real and imagined.

In chapter 4, “Imprints: Hybrid Memories, Interior Journeys,” Gertsman engages with concepts of imprinting and sealing and how they connect with memory making. Circling back to her earlier discussion of medieval theories of vision, she extends the metaphor of stamping to the viewers, as vision was believed to be a tactile process that imprinted both the eyes and the memory. Citing Paul Crossley’s work on Chartres, Gertsman invokes the concept of ductus, where one inscribes oneself among sacred spaces through examination of the formal qualities of an image (164). The Shrine Madonnas thus enable the viewer to go on an imaginary pilgrimage, “traveling down associative devotional pathways from one mnemonic compartment to the next” (167). Gertsman demonstrates this concept of ductus through a case study of Notre Dame de Quelven, a monumental late fifteenth-century Shrine Madonna in Brittany. She describes the possible visual pathways that the viewer would take as the shrine is opened, and the ways in which the narrative images might act as a memory map. Making and unmaking occurs in a continuous cycle, both within the object itself, as the doors are opened and closed, and within the viewer’s own body, as narrative images are witnessed and decoded. Gertsman argues that it is through this process of viewing, and the resulting physical changes in the viewer’s body, that the devotee can “effectively inhabit [Mary’s] womb” (176), the vehicle for salvation.

A postscript, “The Excavated Body,” looks at images from the following centuries that reflect upon the themes of unfolding and disclosure. I found this section to be a less than satisfying epilogue, as many of the examples presented—a sixteenth-century flap woodcut of a female spinner, an eighteenth-century wax female body with moveable parts, and a modern-day “fembot” constructed to serve beer—serve to highlight the differences between Mary and all other women. The question of how medieval viewers reconciled this difference, especially in light of the range of images that presented other women’s bodies as sites of danger and anxiety, is never fully answered.

As Gertsman notes in her introduction, she has chosen to treat these objects as “palimpsest[s] of signification” (13), inscribing upon their bodies many possible meanings and interpretations. This multiplicity of meanings echoes the multitude of metaphors ascribed to Mary in the Middle Ages and provides for a thought-provoking journey across the landscape of late medieval devotion. The case studies are the moments when Gertsman is able to demonstrate the kinds of close looking that such sculptures invite, and I would have welcomed more instances of close looking at other Shrine Madonnas included in the checklist at the back of the book but not discussed in the text. Images of all of the sculptures included in the checklist would have been useful in this regard, allowing for opportunities to compare and contrast the sculptures and to better understand the variety of approaches to the Shrine Madonna type.

A finalist for the College Art Association’s Charles Rufus Morey Book Award in 2016, Worlds Within is beautifully produced, with many full-color reproductions and high-quality paper that makes for a sumptuous reading experience. The inclusion of a gatefold of the Rhenish Shrine Madonna at the Met is a clever touch, allowing readers to enact an approximation of the opening and closing of the shrine. This sense of playfulness, in both the text and the book itself, reminds us that late medieval devotion itself was often playful. It is a welcome approach, and the wide range of possible approaches to the Shrine Madonna presents a model for interdisciplinary research. Worlds Within is an important contribution to current scholarship on late medieval devotion and will surely become a standard text for students and scholars alike.

Johanna Seasonwein

Senior Curator of Western Art, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon