- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

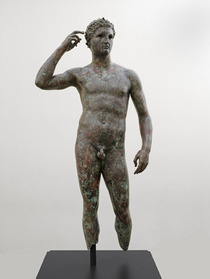

The exhibition Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World presented significant examples of monumental bronze sculpture from the Hellenistic period (323 BCE–27 CE). Curated by Jens Daehner and Kenneth Lapatin, both of the Getty Villa, Power and Pathos not only examined the historical context of these Hellenistic bronzes, but also addressed the importance of bronze as a medium for depicting the movement and expression that are characteristic of Hellenistic art. Although monumental bronze sculptures were highly valued in antiquity, they rarely survive today, and the few remaining examples are often displayed individually in museums. As Daehner and Lapatin emphasize, “being able to see and study more than one or two bronze sculpture at a time is exceptional” (21), and as this exhibition provided the occasion to view nearly fifty objects, it was an unprecedented opportunity to explore issues of style, technique, and context. Remarkable in its scope and content, Power and Pathos surpassed other shows thanks to significant loans from over thirty museums and thirteen different countries, the result of collaboration between government authorities and museum directors, and was particularly notable for the number of works that had never before left their country of origin. While the visually stunning objects would themselves be reason enough to visit, one was rewarded for careful attention to the underlying connections between these varied sculptures, which testified to the importance of bronze as a unique artistic medium.

Power and Pathos was the most recent in a series of exhibitions and scholarly publications that have focused on ancient, and specifically Hellenistic, bronzes. Owing partly to bronze’s unique composition as a copper alloy, bronze studies have often focused on technological analyses of the material, examining casting processes, chemical properties, and methods of production. With its broad span, Power and Pathos sought to alter the narrative of bronze studies by questioning how the medium may have been particularly well suited to the goals of Hellenistic art, such as realism and expression. To accomplish this objective, the exhibition included an impressive variety of material ranging from the more familiar, such as L’Arringatore (The Orater), a portrait of the Etruscan/Early Republican Aule Meteli (cat. 33), to several pieces discovered more recently, such as the bronze torso found off of the coast of Kythnos in 2004 (cat. 14). Not all works in the show were monumental; several small-scale statuettes provided an idea of the ways in which artists used bronze or illustrated themes not found in larger sculpture, for example the small artisan (cat. 36) or young boy (cat. 34). In all cases, even well-known objects from textbooks or displays in other museums found new meaning when displayed with their bronze peers.

Situated in the special exhibition galleries off of the East Garden Court in the National Gallery, the exhibition began with an introduction attesting to the significance of ancient bronze sculpture despite its rarity in the archaeological record. A limestone statue base signed by Alexander’s court sculptor Lysippos (cat. 1) started the show, reminding viewers that the fewer than two hundred surviving examples of monumental bronzes are only a very small portion of those formerly in existence. Although such works were common and highly valued in antiquity, they are rare today due to circumstances of survival—primarily because bronze, like other metals, was melted down throughout history for reuse in other contexts. The sculpture that does survive is often the result of accidental events, most significantly shipwrecks, or deliberate preservation, as in the case of the Terme Boxer (cat. 18), which was intentionally deposited on the Quirinal Hill in Rome.

Following the introduction, the exhibition proceeded with thematic galleries that emphasized the representational innovations occurring throughout the Hellenistic period when the shift from idealized, Classical forms to realistic, expressive bodies occurred. Beginning with the image of Alexander (cat. 2), the second gallery introduced the importance of the ruler culture in the Hellenistic period and the subsequent need for realism in sculpture, particularly in representations of individuals. Bronze, as opposed to marble, was the desired material for depictions of humans, while marble remained preferable for the divine gods. The ability of bronze to achieve this desired realism became clear throughout the remaining galleries, which proceeded according to several thematic categories including likeness and expression, images of the divine, and retrospective styles. A gallery on the male body explored depictions of the athlete, specifically the Apoxyomenos type, and made visible issues of both replication and representational standards in the post-Classical period.

In conversation with these visual themes was the continuous emphasis on the medium of bronze. While only one introductory wall text was devoted specifically to issues of material and technique (i.e., a panel diagramming the lost wax-casting procedure), the remainder of the exhibition continually, if a bit subtly, addressed the medium’s ability to capture the dynamic and detailed representations characteristic of the period. A juxtaposition between the marble Bust of a Bearded Man (cat. 30) and the bronze Arundel Head (cat. 27) highlighted this difference. The marble bust displays features typical of bronze sculpture that would have been more difficult to achieve in stone, such as incised eyebrows and finely outlined lips.

A special emphasis in the exhibition and accompanying catalogue was the theme of replication. The nature of bronze makes it easily reproduced through casting, and in several instances multiple versions of the same statue were on display. The Apoxyomenos was perhaps the most discussed, but the most visually stunning was the bronze herm of Dionysus from the Mahdia shipwreck (cat. 45) and a second sculpture of the same subject from the J. Paul Getty Museum (cat. 46). The herms are remarkably similar in iconography, but were unfortunately placed on opposite sides of a (albeit small) room, missing what would have been an excellent opportunity for close looking and side-by-side comparison. (The herms in this exhibition have been part of recent scholarly discussion. See the dialogue between Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway and Beryl Barr-Sharrar: Ridgway, “Review of Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World,” Bryn Mawr Classical Review [BMCR], 2015.09.02; Barr-Sharrar, “Response,” BMCR, 2016.02.29; and Ridgway, “Response,” BMCR, 2016.02.47.)

Absent from the National Gallery version of the exhibition were several of the most anticipated pieces, including the Terme Boxer (cat. 18) and the Croatian Apoxyomenos (cat. 41); however, they were replaced by formidable stand-ins, most notably the running youth from the Villa dei Papiri, which provided an excellent addition as its striding form is a near-perfect illustration of both the dynamism and technical achievement made possible by bronze. The figure’s outstretched arms and lunging form demonstrate the remarkable ability of bronze to conform to dynamic poses without the supports necessary with heavy marble.

The full impact of the exhibition cannot be realized without the accompanying catalogue, which engages more fully with the themes and questions brought to the surface in the galleries. The catalogue expands far beyond the exhibition’s focus on representation, with eleven essays on such topics as technique, material, discovery, and conservation. In addition, the fully illustrated catalogue follows the exhibition and is arranged according to themes, which help to solidify the same topics that were present in the show. The catalogue in itself is a visual pleasure with over fifty full-page, glossy images and high-resolution details. Easy-to-read maps and an appendix of technical analyses help to illustrate the allure of bronze during the Hellenistic period—so much so that one wishes more of these scholarly insights could have been included in the exhibition.

A feast for the eyes, Power and Pathos succeeded in demonstrating the significance of bronze and defining the trajectory of monumental sculpture in the Hellenistic period. With this unprecedented display, the exhibition was of interest to specialists and the general public. Each individual object was extraordinary, but as seen together in the exhibition they were visual testaments to the power of bronze to represent and affect experience.

Elizabeth M. Molacek

Post-Doctoral Curatorial Fellow, Harvard University Art Museums