- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

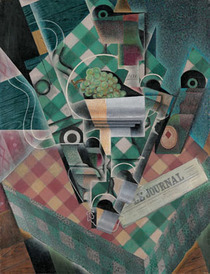

Cubism constitutes one of the greatest revolutions in the history of Western art, on a par with the one launched at the beginning of the fifteenth century by two other young artists, in another booming economic and cultural center permitting radical innovations within the realms of the arts and sciences—though Florence, at the time that Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello reached their first heights in the early quattrocento, was an undoubtedly quieter place than was early twentieth-century Paris when Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque reached theirs.

Why is such a comparison worthwhile, one might wonder? For one, because both cases involved two artists who, while competing fiercely, profoundly inspired each other as they broke away from the living visual tradition around them. Additionally, it seems to me that the political, social, cultural, and economic conditions encountered both in Florence and Paris have a great deal to do with the emergence of these new artistic languages, namely the early Renaissance and Analytic Cubism. The triumph of the merchant class and the administrative know-how and hunger for glory of the guilds enabled the flowering of the Renaissance in Florence; and the amount of images and ideas being bandied around Paris, hothouse of both technological and scientific breakthroughs, makes it the vital locus for the development of Cubism from 1908 to 1914, as the French capital was a place where avant-garde practice mattered, and where the ambitious artist who played her or his cards well could show work and cultivate an audience.

Significantly, however, the Cubist style was developed by outsiders—one from Málaga, Spain, and the other raised and trained at Le Havre, about 120 miles to the west of Paris—who were, because of this, particularly sensitive to the wide variety of data to which they were exposed. This is not unlike the conditions that existed when the Baroque style was launched by the outsiders Annibale Carracci and Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, circa 1600, in another great capital, Rome—though those artists did not establish the type of intellectual partnership Brunelleschi and Donatello had formed, and that Braque and Picasso would.

Viewers are not encouraged to make connections of this sort at the Cubism: The Leonard A. Lauder Collection exhibition and in its accompanying catalogue. The tradition out of which Cubism arose is not at all addressed in the heavy publication, and the “City of Light” as pulsating metropolis is barely acknowledged. But the place where conventions are shattered through the introduction of new paradigms—and with renewed vigor since the early Enlightenment—is the very place to find an entirely new art emerge that, for the first time in the history of Western art (ornament excluded), aimed to give visual form to extreme forms of ambiguity and complexity. To such an extent, in fact, that a century later it can still be challenging to decipher exactly what we are looking at in certain Cubist works. Romanesque and Mannerist art did not reach comparable degrees of visual opacity.

What I am saying here has undoubtedly been stated elsewhere and more eloquently than space permits, but even if so, shouldn’t this fascinating story be retold with a twist at the beginning of this exhibition and in the essay opening the catalogue? Instead, Cubism is presented as a fait accompli, coming about practically in a vacuum, as it were, the catalyst being Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Picasso’s bewildering transitional painting. But Cubism did not emerge out of nowhere; instead, it engaged head on with the history of art. In Analytic Cubist painting, solid form was gradually abandoned in favor of incomplete armatures built up of facets and signs, opening up the bodies to the surrounding space, and with seemingly contradictory transitions in shading—a more rabidly anti-academic type of painting can hardly be imagined.

Allow me to expand a little more on Cubism and the history of art. The mark as signifier—meaning one thing in one place within the composition, and something different in another—can be traced back to early Impressionist pictures by Claude Monet. However, Analytic Cubism moves away from the rich color scheme of Impressionism, Postimpressionism, and Fauvism—styles that had already gone far into the dematerialization of form—toward beige, brown, and gray tonalities, which in my view (besides pursuing Leonardo’s goal of tonal unity) were part of a playful attempt to make an art for the museums, à la Rembrandt. Impressionism had, after all, landed in the national collection at the Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, through the bequest of the painter and collector Gustave Caillebotte, and by 1908, three among the four principal Postimpressionist painters were celebrated through important posthumous retrospective exhibitions.

The oval format of certain Cubist pictures that focus upon the still-life motif by lobbing off the corners of the traditional rectangular painting—which Picasso and Braque covered with feathery brushstrokes rich in atmosphere, as they had nothing else to place there (I echo William Rubin here)—that format (Picasso, The Scallop Shell: “Notre Avenir est dans l’Air,” 1912) goes back to the French Rococo, while the much rarer circular format (not represented in the Lauder collection) evokes the Renaissance. However, it is worth noting that the Rococo is about pleasure, and that so much Cubist painting is so clearly not about that—the sitters (who are almost always alone) are melancholic, the early landscapes forlorn, the still lifes at times ominous. Why? And why is this passed over in the exhibition catalogue? Also, although landscape—a classical genre rediscovered during the Renaissance—was crucial to Cubism’s early development (Braque, Trees at L’Estaque, 1908), it eventually vanished from the pre-war work of Picasso and Braque. Why did that occur?

The still lifes—another Renaissance rediscovery—may show a sliver of newspaper, and newsprint may be included in certain drawings showing either still life or the figure (Picasso, Head of a Man, 1912), thereby introducing istoria (edifying narrative) through the back door, as it were. For, while it does so, Cubism carries on the avant-garde’s move away from history painting (long considered the highest form of painting, since being so proclaimed by Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise On Painting of 1435), an act of rebellion that was initiated circa 1848 by Gustave Courbet. The newsprint becomes a kind of black-on-white pointillism, a playful response to Georges Seurat, who was steeped in color theory and had given—as Alberti had—new meaning to painting as science. The news (les nouvelles) included in this new art (un art nouvel) also alludes to time streaming by.

The exhibition celebrates a promised gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Leonard A. Lauder of eighty works by Picasso, Braque, Juan Gris, and Fernand Léger spanning 1906–24, the first two artists being the co-inventors of the style that took off like wildfire circa 1911, and the latter two artists being among the most inventive ones working within the language of Cubism. With this promised gift of paintings, drawings (often cum papiers collés, or vice versa), and sculpture, New York City will become—thanks to the combined holdings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum—an essential place for deepening one’s understanding of the developments leading to the emergence of the Cubist style in 1908, and that style’s evolution over the course of the next six years; that is, until the First World War tore Braque away from his comrade-in-arms, Picasso, leading to one of the great what ifs in the history of twentieth-century art. (The dialogue between these artists was not resumed once Braque returned—severely wounded—from battle.)

Coincidentally, perhaps, this exhibition opened exactly one century after the fascinating artistic exchange between Braque and Picasso was concluded. That dialogue was the subject of an intellectually riveting and profoundly moving exhibition, Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism, organized by Rubin a quarter of a century ago (1989) for the Museum of Modern Art. It is unfair to compare this exhibition to the earlier one, as Lauder could only collect what remained available to him and met his standards, while Rubin could draw from a wide variety of public and private collections. Nevertheless, I laud Lauder’s focus upon the production of a limited number of years in the careers of the two Spanish and two French Cubist masters.

That said, Lauder’s shadow looms too large. The collection is gone over exhaustively and with far too much reverence in the catalogue, as if all works were of equal merit, making for painfully tedious reading at times, as the essays are almost all structured in the same way, despite the gathering of close to twenty essayists, many among them well known. Too few risks are taken, though Cubism was all about disrupting the status quo. Dryness prevails, though Cubism was packed with humor and was nothing less than visually and intellectually thrilling.

Additionally, no preliminary explanation is given about how the works are divided over the twenty-two catalogue essays. As the works in the collection are not illustrated in chronological order, but instead in the order in which they are discussed in the essays, and furthermore are interspersed with lots of comparative material, one can spend some time fishing around to find a specific image. Surely, this book could have been made easier to navigate.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the first gallery was reserved for works by Braque, the second for works by Picasso, the third almost exclusively for Braque, the fourth for mostly works on paper by Picasso and Braque; all the works by Gris were displayed in the fifth gallery, works by Picasso and Braque were featured in the sixth room, and the seventh and final gallery was devoted to the work of Léger. Marvelous risk-taking was displayed by all throughout these galleries. One only wishes that it would have been possible to experience these works as others first got to see them, and not only because one would like to see them in better physical shape (the newspaper collage in the drawings, for example, has turned brown, thereby disrupting the values throughout these compositions). Indeed, one would like to recapture the unsettling power of these works, instead of being almost conditioned to take these experiments in modernism for granted. Cubism is now widely appreciated, judging by the crowds in the galleries.

More questions remain. Why did these artists hardly ever experiment with different types of pictorial support during the years under consideration—such as wood, metal, or glass (the first two materials were, however, deployed by Picasso in his painted Cubist sculpture, which proved to be of such enormous consequence)—in order to achieve different textural effects, other types of luminosity, and with the glass, forms that become even more slick or diaphanous than they can appear on canvas. Were the frames around the paintings selected—either haphazardly or after careful deliberation—by the artists, their dealers, or by collectors? Which brings us to the early marketing and collecting of these deliciously strange things, about which the catalogue says very little. I ask so much because Cubism remains so very exciting. Happily, more remains to be done.

Michaël Amy

Professor, School of Art, Rochester Institute of Technology