- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Nazi officials confiscated more than twenty-one thousand works of art from German public collections during the infamous “degenerate art” action of 1937–39. Nearly six hundred of these stolen works appeared in the hastily organized propaganda exhibition, Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art), which opened in Munich on July 19, 1937. The exhibition drew an estimated two million visitors to the cramped and shabby galleries of the Munich Archaeological Institute, and it traveled, in modified form, to eleven cities throughout Germany and Austria between 1937 and 1941. Nearly eight decades later, the Nazi attack on modern art continues to draw crowds. In a compact and visually elegant exhibition at the Neue Galerie, German curator Olaf Peters has selected approximately fifty paintings and sculptures, thirty works on paper, and a number of posters as well as film footage, photographs, postcards, and other ephemera that together recreate the “aura” of the Entartete Kunst exhibition, without adopting its degraded tactics of installation and display. Instead, through a series of provocative formal juxtapositions, the New York exhibition extends to the visitor a tantalizing invitation: “You be the judge.”

This position of aesthetic judgment requires historical context, which the exhibition offers through an engaging if occasionally polemical audio-guide commentary. One learns that the Nazis did not coin the term “degenerate art,” but, rather, that they borrowed and institutionalized a concept that had been circulating in medical and cultural discourse since the late nineteenth century. Peters devotes the first essay of the handsome and comprehensive exhibition catalogue to the history of these “degeneration” theories in Germany, focusing on Max Nordau’s two-volume text, Entartung (Degeneration, 1892–93). Nordau, a trained physician who had studied with Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris, diagnosed degeneration as a mental illness and targeted modern artists as diseased, decadent corrupters who should be separated from what Nordau and his Social Darwinist contemporaries viewed as the healthy “body of the people” (exhibition catalogue, 17). This notion of distinction is central to Peters’s scholarly reading of Nordau, and it is a guiding principle of the Neue Galerie exhibition. This strategy offers to the catalogue reader a textured and novel understanding of the manifold origins, the conception, and the consequences of Nazi cultural policies that led to the “degenerate art” action and exhibition in 1937. As an installation concept, it translates into an equation between the separation of artworks and the eventual segregation of Jews and other persecuted groups.

Entering the exhibition on the museum’s third floor, two oversized photomurals dress the walls of a long, narrow hallway: on the right side, a queue of visitors waits to enter the Schulausstellungsgebäude in Hamburg during the traveling exhibition of Entartete Kunst in the winter of 1938. On the left wall, a line of Carpatho-Ukrainian Jews arrive by train at Auschwitz-Birkenau in May of 1944. The intended analogy between these two images is clear: the earlier event foreshadowed the later one. As an attempt to implicate the contemporary exhibition viewer in the process of embodied looking, and thus to activate her or his historical consciousness, this approach is effective—evoking, if perhaps unintentionally, the long lines wrapped around the Neue Galerie during the run of its own blockbuster exhibition. But as an installation strategy, the insistence on blunt causality may be distracting, a distillation that undermines the nuanced historical essays contained in the exhibition catalogue and in Peters’s own scholarship on the complicated relationship between the cultural politics of the late Weimar Republic and those of the Third Reich (Olaf Peters, Neue Sachlichkeit und Nationalsozialismus. Affirmation und Kritik 1931–1947, Berlin: Reimer, 1998).

Other curatorial juxtapositions prove to be more effective. Nazi propaganda posters hang high and low throughout the third-floor entrance hallway, clamoring for attention: the stark diagonals and bold tones of these political posters and exhibition placards demonstrate how the National Socialists adopted modernist advertising strategies to their own propagandistic ends. (A sarcastic exhibition poster condemning the “cultural documents of bolshevism,” designed in 1936 by Hans Vitus Vierthaler, might otherwise be mistaken for a vintage Bauhaus product.) At one end of this hallway, a single dissenter halts the procession of Nazi-sanctioned imagery: hung high above eye level, Oskar Kokoschka’s self-portrait lithographic poster both reflects and demarcates the historical terrain leading up to the Entartete Kunst exhibition. The face registers wear and strain, and bold black marks fix the agitated body against a saturated orange background. The finger of the left hand directs attention to a livid gash that scores the gaunt ribcage. The Austrian Kokoschka created this image for the influential Expressionist magazine Der Sturm, in 1910, and it later hung alongside other works of “degenerate art” in the 1937 Munich exhibition. By this time, Nazi officials had identified 1910 as the origin date for modernist works eligible to be purged from German public collections; in total, nearly four hundred of Kokoschka’s works would be confiscated.

A large end gallery anchors the third floor of the Neue Galerie exhibition; careful viewers will notice the subtle, two-toned wall treatment separating works of “degenerate art” from examples of officially sanctioned artworks, some of which appeared in the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition) of 1937. This celebratory art show opened in Adolf Hitler’s newly constructed Haus der Kunst in Munich, on July 18, just one day before the Entartete Kunst exhibition premiered in degraded conditions nearby. At the Neue Galerie, two large, allegorical triptychs perform the central roles of compare and contrast in this divided gallery: Adolf Ziegler’s The Four Elements (1937) and Max Beckmann’s Departure (1932–35). Much critical attention has been paid to Ziegler’s nude Aryan maidens—this painting, as the audio guide states, eventually hung over Hitler’s fireplace in the Führerbau; New York museumgoers may also remember it as one of the culminating pictures in the 2010 Guggenheim exhibition Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918–1936. By displaying Ziegler’s naturalistic, academic confection alongside Beckmann’s dark, modernist world of myth, the museum encourages viewers to reach a confident aesthetic judgment: that the Ziegler is outmoded realist kitsch, and that the Beckmann is a bold standard-bearer of modernism. But these stylistic conclusions cannot be so easily assumed. Indeed, as the critic Philip Kennicott asserted in the Washington Post, what the Neue Galerie offers in this exhibition is an alluring, but ultimately also a problematic, invitation to “enjoy an oasis of moral clarity about the connection between art and politics” (Philip Kennicott, “Crowds Flock to Neue Galerie in N.Y. to See Art Condemned As ‘Degenerate’ by Nazis in 1937,” Washington Post [May, 24, 2014]).

Part of the danger in accepting this proposition is that it contradicts Peters’s own conclusion—supported by copious primary research and archival evidence—that Nazi cultural policy was plagued by infighting and prone to radical shifts in judgment. The tools of Nazi aesthetic distinction were, at best, haphazard, confused, and contradictory. In the Neue Galerie exhibition, Richard Scheibe’s sober, upright Decathlete (1936), a monumental sculpture that appeared in the Great German Art Exhibition, squares off against a set of “degenerate” sculptures by Ernst Barlach: the pensive Reader (1936), who casts his gaze downward and slumps his shoulders toward an open book, and The Berserker (1910), a crouched figure with fist clenched and sword brandished behind his head. The Berserker impressed the future Nazi cultural minister, Joseph Goebbels, when he first saw it in 1924 at a Cologne exhibition, but by the late 1930s, Goebbels had rejected his previous taste for German Expressionism. In a series of incisive catalogue essays, Peters and his fellow authors demonstrate how the malleable Reich Propaganda Minister shaped his views to suit the Führer’s more traditional aesthetic demands, which preferred the “clarity” of Neoclassical architecture and the naturalism of nineteenth-century Munich genre painting.

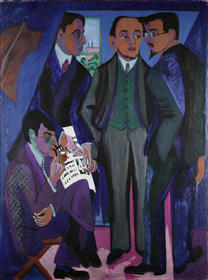

The adjacent gallery turns to the city of Dresden, where both Expressionism and its modernist successors, Dada and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), flourished in the years between 1905 and 1933. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s stunning A Group of Artists (The Painters of the Brücke) (1925–26) reunites four members of the avant-garde movement in a cramped Expressionist interior: Otto Mueller crouches in a vibrant, eggplant-hued suit jacket, while Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff stand to the side with pursed lips and inscrutable expressions. Kirchner, in a self-portrait, lurks apart from his three friends, clutching a copy of the controversial Brücke pamphlet he published shortly before the group disbanded in 1913. In addition to this master chronicle of Expressionism, the Dresden gallery includes Heckel’s darkly collapsing Barbershop (1913) and Beckmann’s moody Cattle in a Barn (1933). Karl Caspar’s strange, almost toxically vibrant canvas, Resurrection/Easter (1926), shows that Expressionism persisted well into the 1920s, even as the cool realism of the New Objectivity began to take hold in cities such as Dresden, Berlin, Karlsruhe, and Mannheim. The work of Expressionist painter Christian Rohlfs, likewise, both startles and delights: his lively Acrobats (ca. 1916) tumble and stretch and merge into gender-bending bodies. Perhaps for this reason, Rohlfs was one of the most represented artists in the Entartete Kunst exhibition, with seventeen paintings in total; three of these works are here on view.

Another gallery explores the attack on the Bauhaus in the late 1920s and early 1930s: examples of sleek modernist furniture designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer, for example, stand alongside paintings by Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Lyonel Feininger, whose Gelmeroda II (1917) crackles and shines in a riot of caustic yellow and brown tones. Harassed for years by its conservative opponents, the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to Dessau to Berlin and was forced to shut down entirely in 1933. A large wall vinyl of Iwao Yamawaki’s photomontage, The Attack on the Bauhaus (1932), presents an incisive commentary on this history, in which the medium of photomontage became a key mode of artistic resistance that persisted into the Third Reich. In a small side gallery, one finds additional stories of “Collaborators and Combatants”—delicate works on paper by Ernst Barlach and Emil Nolde, both of whom receive extended treatment in the exhibition catalogue.

The exhibition concludes in an elegant second floor gallery, where large, bold portrait paintings by Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, and other “degenerate” artists hang below a row of ornate, but empty, frames. (These evocative blank spaces stand in for destroyed or still-missing works of Nazi-looted art.) The sound of a shrill, disembodied voice projects from the room’s far corner, where Fritz Hippler’s anti-Semitic propaganda film, Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew, 1940), plays on a loop on a small video screen. Hippler used modern editing techniques to craft a reactionary visual narrative of degeneration: in one macabre cross-fade, an image of Nolde’s Eve (1910) seems to burn through the head of the Christ child in Cranach’s Madonna under the Apple Tree (ca. 1525). Kokoschka’s Self-Portrait as a Degenerate Artist (1937) hangs on an adjacent wall and demonstrates how one artist sought to subvert and challenge the Nazi conflation of modern art and physical-formal degeneration. Dressed in a cap-sleeved blue tunic, jaw set defiantly, Kokoschka stares outward with his arms crossed to display a pair of large, fleshy, almost menacing hands. Lovis Corinth’s stunning Portrait of Georg Brandes (1925) offers a final and telling example of how the Nazis sought to assign a deviant pathology to modern art. In a hate-filled speech that opened the original Entartete Kunst exhibition, Ziegler asserted that Corinth had only attracted the interest of German museums after suffering a stroke, when he began to produce “diseased and incomprehensible daubs” (exhibition catalogue, 36). Ironically, of course, the artworks that Ziegler and his Nazi colleagues defamed in Munich would later form a canon of German modernism—a “narrowed modernism,” as Ruth Heftrig terms it in the title of her highly original catalogue essay, in which “degenerate” would become a badge of honor.

Shannon Connelly

independent scholar