- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

June Wayne’s exhibition Narrative Tapestries: Tidal Waves, DNA, and the Cosmos symbolized her triumphant return to the city of her youth and marked the re-opening of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (AIC) permanent textile galleries after a five-year renovation. The show featured eleven out of twelve exquisite tapestries Wayne created in collaboration with three different French ateliers from 1970–74 led by the following artists: Pierre Daquin, Camille Legoueix, and Giselle Glaudin-Brivet. An exhibition catalogue accompanied the show with informative essays by Christa C. Mayer Thurman, curator emerita of the Department of Textiles at AIC, and Wayne, as well as high-quality color illustrations of each exhibited work.

Wayne is best known as the founder of the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in 1960 in Hollywood. After ten years Tamarind was relocated to the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and Wayne found an opportune moment to explore a medium that holds strong parallels with lithography. Encouraged and assisted by her close friend Madeleine Jarry, the Inspecteur principal Mobelier national et des Manufactures nationales des Gobelins et de Beauvais, Paris, Wayne was introduced to commercial galleries and ateliers to help the artist actualize her envisioned project. While the two media may appear vastly different, Thurman explains there is a strong relationship in both process and visual qualities. For Wayne, like printmaking, tapestry permits a sensuous surface, vast scale, and subtle enough details to capture the imagery Wayne executes in prints, along with providing a malleability of surface not possible with lithographic stone. More importantly, creating tapestries demands a significant partnership with each atelier, which is also essential to any lithography workshop. For example, after executing each image in full-scale cartoons, Wayne regularly consulted with weavers in order to ensure the precise shades and colors of wool were being used for each design (8–11).

Given that most audiences have little knowledge of the labor and techniques needed to make tapestries, the exhibition helpfully began with photographs illustrating how these textiles were created, from the drawing of the cartoon, to the selection of threads, and lastly the weaving on the loom. Further, samples from the three weavers who worked with Wayne were featured.

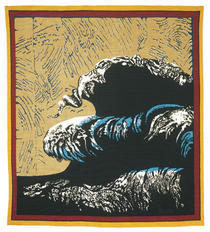

After taking in the technical aspects of tapestry making and some background on Wayne’s artistic career, exhibition goers descended the majestic stairs into the main exhibition space. Wayne’s large-scale tapestries came into view and projected beautifully against the dark grey walls of the gallery. Pieces dominated by bright color were carefully alternated with those primarily executed in black and white, easily drawing the visitor’s eye through the space. At first glance, it was hard to believe that these works were woven with thick cotton and wool. In fact, the newly conserved tapestries offered lush colors, very subtle gradations of hue, and forms that projected powerfully from the walls. For instance, Col Noir (Black Chain) (1973) features a DNA chain hovering against light blue skies set above a rocky landscape, articulated in a way that one feels the sensation of gritty rock and sharp angles of a cliff face. Overall, the subject matter ranges from such scientific representations to images of dramatic waves—such as Grand Vague Bleue (Large Blue Wave) (1973)—and surreal landscapes, for example, La Journée des Lemmings (Lemmings’ Day) (1973); they also frequently derive from earlier prints created by Wayne that examine the same themes.

In the midst of pursuing this tapestry series, Wayne began offering her “Joan of Art” workshops in 1971 that taught women artists how to promote themselves. Wayne’s association with a growing feminist movement and simultaneous choice of a medium traditionally associated with women might tempt some to conflate her production in tapestries with the work of feminist artists in California, such as Judy Chicago, who sought the revival of the domestic arts of embroidery, china painting, and quilt-making. Wayne even exhibited At Last a Thousand (1972) in a solo show held in 1975 at the woman artists’ cooperative Artemisia Gallery. At the AIC, Wayne’s tapestries were shown in a gallery adjacent to a selection of fiber works from the institute’s permanent collection, featuring examples from noted artists Anne Wilson, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Sheila Hicks, Lenore Trawney, and Claire Zeisler. However, here Wayne does not claim any association with feminist art and is insistent that these works be called tapestries instead of “fiber art.” Acknowledging that fiber art “jumped over the convent wall” (33), Wayne also recognizes that the phrase was invoked as a way to elevate this art form over craft and resist its gendered associations with the domestic or amateurism. Yet for the works on display, she argues that the medium and nomenclature of tapestry is important not only for its reliance on collaboration and relationship to printmaking (as noted above), but also how it creates an arena for narratives to be constructed and dialogues stimulated with the viewer (35).

In particular, the medieval tradition of tapestry becomes a stage for contemporary questions in science that resonate well beyond the early 1970s when Wayne’s tapestries were originally made. In the catalogue, Thurman explains that the waves that figure in five of the eleven tapestries derive from Wayne’s childhood memory of studying Lake Michigan near the Museum of Science and Industry (26). Created from the perspective of a viewer standing in the water, on one level they link Wayne to mid-century Chicago artists such as Gertrude Abercrombie and Julia Thecla who were similarly fascinated by this vast body of water, using it as a frequent setting for their surreal narratives. However, given Wayne’s emphasis on science, tapestries such as Lame du Choc (Shock Wave) (1973) can also be read as referencing the recent history of global warming and increasing incidents of tsunamis. Verdict (1972) features a rainbow-colored DNA helix chain as a dominant motif, hovering above a very steep rock face that reveals the “x” spine of the DNA structure on the lower left of the image (20). This work, along with Col Noir, was inspired by a 1969 visit with Jonas Salk at his Institute where Wayne was first introduced to a DNA sample of bacteria (19–20). In titling the tapestry Verdict, Wayne suggests that the genetic code is an inherited verdict and seems to understand how it would become ubiquitous in twenty-first century culture, whether the lynchpin for determining who committed a crime or fundamental to reproductive technologies.

Visa (1973) features Wayne’s colorful fingerprint looming against a stark black background and alludes to strategies of identification. First, it functions as Wayne’s ultimate stamp of personal identity. At the same time, it reflects an escalating surveillance society post-9/11 with the fingerprint becoming an emblem for new devices increasingly used to control immigration and travel. At Last a Thousand (1972) is equally prescient by alluding to struggles with nuclear power and energy. The tapestry presents a beautiful and vast cosmos, composed of a white circular core with arteries radiating in subtle and varied gradations of grey. However, the image’s lovely and intricate details actually illustrate the last moments of an atomic explosion, existing as a grim reminder that nuclear weaponry still remains a fundamental issue. In all cases, Wayne creates an impressive tension between beauty and her fascination with science, yet implies that a confidence in progress can result in negative consequences.

The catalogue for the exhibition plays a significant role in expanding the discourse surrounding Wayne’s production. Thurman’s essay carefully outlines the artist’s content, methods, influences, techniques, and origins, and Wayne’s personal essay astutely conceptualizes her place within larger conversations of contemporary art. Although Robert Conway and Arthur Danto published a catalogue raisonné on Wayne in 2007, most major museums have neglected her practice not solely because of her gender but more likely due to her dedication to printmaking and figuration. Therefore, the publication suggests that the Art Institute of Chicago recognizes the need for a more comprehensive and complex understanding of U.S. art and its participants.

For this reviewer, the only disappointment is how little known the textiles department is to most visitors to the museum. Located in basement galleries, it is a site many people seem to stumble upon after getting lost looking for the cafeteria. It is hoped that the wonderful works featured in these collections, as well as upcoming special exhibitions, can find a greater dialogue with other areas of the museum and in turn prompt additional and compelling artistic dialogues. Certainly, extending the closing dates of June Wayne’s Narrative Tapestries from early February to mid-May was a promising sign that the museum is committed to raising awareness of its newly opened galleries.

Joanna Gardner-Huggett

Associate Professor, Department of the History of Art and Architecture, DePaul University