- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

The Record: Contemporary Art and Vinyl at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University is, quite appropriately, a mix. And, like any good mix, the exhibition includes perennial hits, lesser-known works by familiar artists, and more than a few unknown gems. Drawing upon vinyl records as “metaphor, archive, icon, portrait or transcendent medium” (as described in a wall text), the exhibition offers a wide-ranging view of how this single object has remained a catalyst for visual artists over the past forty-five years and, as all exhibitions should seek to do, merges a rigorous curatorial program with an almost guilt-inducing quantity of pleasure.

Curator Trevor Schoonmaker’s great triumph is his recognition that records are not simply things, the material means to a listening end. Like records themselves, with their vinyl discs, slip covers, liner notes, and engraved sounds, the exhibition is an audio-optical-tactile cornucopia, a repository of cultural memory and nostalgia, and an ever-changing temporal experience. It is, thus, a striking demonstration that exhibitions that limit themselves to the mute display of inert works of visual art in a neutral gallery space are missing out on vast wells of potential.

The objects on display, films on view, and sounds that meander through the gallery spaces mobilize records and sound systems in every imaginable way. Revolutionary stalwarts, such as Laurie Anderson’s Viophonograph (1977), remind viewer/listeners that records are to be played—like instruments, with instruments, as instruments—and technical experimentation and innovation are as much a part of this history as the music itself.

Despite its foundational place in the history of sonic and performative postmodernism, Anderson’s is not the earliest work in the exhibition. Jasper Johns’s 1969 Scott Fagan Record plays that part. Having acquired Scott Fagan’s LP South Atlantic Blues by unremembered means, Johns saw Fagan perform at Rutgers University and struck up a friendly exchange with the singer. His print is a sly inversion of the record, using the engraved disc as a printing plate, thus shifting the unheard music from the sculptural to the pictorial, from the sonic to the visual, and leaving an image that calls upon both the geometric structures of Johns’s earlier Target paintings and the molten gesturalism of the Abstract Expressionists. Beyond its material existence, Johns’s work reminds us that music is a public experience, perhaps commenced singly, but fulfilled communally, with records as the nexus of a set of interactions extending beyond their initial purpose of listening into innumerable other media and behaviors.

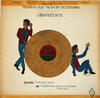

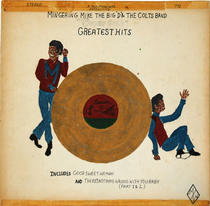

Among the exhibition’s sprightliest works are the slipcovers and LPs painted by Mingering Mike during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Mike, then a teenager in Washington, DC, created for himself a virtual catalog, dense with the iconographies of the soul era: love, seduction, ghetto living, tuxedo styling, Civil Rights, doubled selves, America, superheroes, and kung fu flicks. They are an extraordinary act of self-construction and a joyful cipher of one of the richest moments in American musical history, when records were the makers of cultural identity, and self-determination was central in African American culture, before the disposable objects, identities, and allegiances of the one dollar, one listen digital download.

As importantly, Mingering Mike, with his isolated, invented worlds and his wobbling line, might have been sequestered in the “outsider art” section or left out altogether, as could have been the case with works by Kevin Ei-Ichi Deforest or Alice Wagner. Unfortunately, this separation is often accepted without critique, and Schoonmaker should be lauded for forging on as if the distinction was never necessary (or valuable).

Another artist who employs this homegrown fantastic is Dario Robleto, whose three large-scale works—Lamb of Man, Atom and Eve, and America Materia Medica (2006–7)—steal the show. Five-foot framed squares, each is inset with a border of paper flowers that surrounds a tic-tac-toe board of record covers. The covers are all fictitious, but draw so seamlessly on the language of mid-century record cover design that it takes a few seconds to realize the hilarity of their titles, including The Original Phantom Limbs’ Our Actions are Inconsistent with Heaven and The Treasury of Anti-American Folk Music. These look like the obsessive fussings of a craft-fair funeral director rifling through the Americana bins at a West Virginia swap meet, and their searing mockery of “traditional” American morals is done so adroitly that we are instantly romanced by our republic’s bizarre polyamory of religion, science, and patriotism. If these three ideals have done so much to drive us to fracture, we might find some solace in our shared patrimony of the Grand Ole Opry, Wolfman Jack, and Don Cornelius.

While Robleto’s works may have the most immediate impact, the career of Christian Marclay emerges as the most lastingly potent. His 1980s Recycled Records series calls to mind Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs, though Marclay’s broken and reassembled vinyl records are something a bit more day-glo, Neo-Geo, P&D, junk pile collagist. Marclay truly breaks through with the 1985 performance Ghost (I Don’t Live Today), a video of which is included in the exhibition. Originally performed at the Kitchen in New York, Marclay employs his phonoguitar, a turntable fashioned with a guitar strap that allowed him to play Jimi Hendrix records in the posture of the master himself. The scrapes and hollers that emerge from Marclay’s device are as wondrous as those that were strangled from Hendrix’s Stratocaster, and they recall what Grandmaster Flash already knew, and what others like Mix Master Mike and DJ Qbert have taken intergalactic—turntables are musical instruments, and recorded music causes but one of the sounds they are able to make.

It is here that my only fundamental critique of the exhibition emerges, and what troubles me most is that to many this shortcoming might be invisible. The dilemma is that there are no DJs in the exhibition. No performing musicians of the non-visual artist variety. Granted, the exhibition subtitles itself “Contemporary ART and VINYL,” but I cannot abide the exclusion of DJs—artists whose work would be as legitimate within the context of this exhibition as anything by any other artist. Grandmaster Flash should be acknowledged more publicly, if only for his magisterial “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel,” the sine qua non of turntablism. It is hard to imagine how Public Enemy soundscapists The Bomb Squad and more recent experimentalist DJs like Shadow, with his glorious Endtroducing….., or Spooky (Paul D. Miller), with his Rebirth of a Nation, could not make the cut. When future historians look back to assess the last decades of this millennium, these artists will prove central.

Thankfully there is a great deal of record manipulation going on, even beyond Marclay’s blue-chip appearance. Taiyo Kimura’s 2009 video-performances Haunted by You, while at times a bit too slapstick, quite literally is as beautiful as the chance meeting on a turntable of a stylus arm and an octopus. Ujino Muneteru’s Frankensteining of turntables in his 2006 performance-video Ujino and the Rotators is a wonder to watch and a challenge to listen to, as the artist/DJ spins records, mixed with the electro-spasms of a drill, a blender, a hair dryer, and an infinity of switches and dials. Imagine if John Cage and the Maytag Man had prepared the bow Jimmy Page used on “Dazed and Confused.” Trace, with it, the transnational migration of hip-hop culture, and you will be somewhere in the neighborhood.

Hidden among this cacophonic excitement, one finds Lyota Yagi’s Vinyl (Claire de Lune + Moon River) (2005–9). For nine minutes viewer-listeners watch and listen as a disc of ice, engraved with the eponymous songs, is played successfully on a standard 33rpm turntable . . . until the inevitable takes command and the record starts to melt. The warbling disintegration of the music is a poignant reminder of the passage of time that is both inherent to vinyl and manifest in our culture’s treatment of it. Yagi’s piece is both a loving recreation of the power of vinyl and a quiet elegy to its loss.

Two of Schoonmaker’s smartest curatorial moves are neither on the walls nor in the gallery. First is the exhibition catalogue. Luxuriously illustrated with over four hundred color images, and stuffed with over a dozen essays, the book doubles as an exhibition supplement and an illustrated history of the record and the culture(s) it has engendered. And this is to say nothing of its exhaustive timeline, artist statements and biographies, bibliography, and what Schoonmaker calls his “Extended Playlist,” which lists works that were not available for or included in the exhibition. It is wonderful to be allowed this insight into curatorial research and desire, and Schoonmaker’s sharing of what could have been hoarded away for future projects is an example we would be wise to follow. The breadth and depth of this catalogue are staggering, and the contributors—curators, photographers, historians, academics, musicologists, musicians, critics—represent the broad panorama of scholars and artists who keep records dear to their heart and at the center of their lives. As a catalogue, it is exceptional. As a testament to the ways in which the vinyl record is a universal medium that crosses all boundaries, it is paradigmatic.

Equally exciting is the Cover to Cover installation, which sits just outside the gallery space, in which ten artists (six individuals and two duos) were each asked to create a conceptual work by selecting twenty LPs based on the cover artwork. Visitors are free to look through each artist’s crate, listen to the albums, and search for the linkages. The selected artists are an eclectic and impressive group, including Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, Patrick Douthit (DJ and producer 9th Wonder), Vik Muniz, and Rodney Graham, who includes doubles from his personal collection. Graham’s elegantly simple concept plays to the sympathies of collectors and beat jugglers both, and his selections are exquisite—a few Beatles albums (including one of my own desert island platters, Rubber Soul), Carole King’s perfect Tapestry, and Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde.

Shoonmaker’s great coup lies not in the interactivity of the installation, the pushing of the exhibition beyond the visual arts, or its art-historical rigor. It is in the endless pleasure of seeing, smelling, touching, and listening to the vinyl itself. I have never listened to Black Sabbath’s War Pigs in the tamely hushed halls of an art museum before. Now that I have, I want to do it over and over. Like the entirety of this exhibition, it was a deeply satisfying, genre-bursting experience and one to repeat again and again until the grooves wear out.

Adrian R. Duran

Assistant Professor, Art History, Memphis College of Art