- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Curators Sarah Lewis and Daniel Belasco use a metaphor of alchemy to describe the contemporary works they brought together for The Dissolve, their title for the SITE Santa Fe Eighth International Biennial. The ingredients for the new global media practice they highlight are bodily gestures, advanced digital technologies, and inspirations from early twentieth-century motion picture experiments, resulting in, as the exhibition catalogue states, “new hybrid forms where the homespun meets the high-tech” (20). The six-year process of choosing the final thirty works—twenty-six contemporary and four historical—and conceiving of the spatial and textual accoutrements that would do them justice has produced an exhibition that many reviewers have seen fit to describe as “magical.” The challenge to scholars in the future will be to demystify The Dissolve. If the exhibition succeeds in recapturing something of the awe that early twentieth-century viewers felt before moving images, then what reconfigurations of media have made it possible to profoundly touch the changed sensibilities of contemporary viewers?

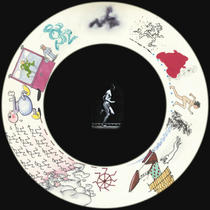

In some instances, a Benjaminian appeal to the outmoded appears to be in play. Impatient viewers lined up at the opening to hand crank George Griffin’s Viewmaster, a digital mutoscope (1976/2007), seduced by the peculiar kind of bodily labor required to drive the digitally animated drawings of anthropomorphic blobs and people. Here the lateral and staccato motions necessary to activate a mouse gave way to the soothing and continuous rhythm of an old-fashioned butter churn. Persistence was rewarded when the seemingly endless strip of cartoon figures running in place suddenly zoomed out to reveal a nineteenth-century Eadweard Muybridge study of a nude male runner in the center of the wheel.

In Kara Walker’s art, the eighteenth-century form of the silhouette is animated not as a historical novelty but as a return of the repressed. In new work (2009) whose narrative borrows directly from historical slave archives, Walker continues to demonstrate that contemporary viewers are capable of investing this archaic form with a surfeit of emotion. Lest the ubiquity of Walker’s work renders it redundant, the curators have carefully placed Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) on the opposite side of the partition. Its shadow puppets, which act out Orientalizing scenes from The Arabian Nights, appear more sinister in light of Walker’s theater of horrors, and her confrontation with the history of racialized representation, in turn, richer and more wide-ranging.

In much of the work on display, the technology is less up-to-date than the ends to which it is used. In Re/trato (2003), Oscar Muñoz simply lets his painted lines evaporate on camera. It is in part political concerns that make this gesture so powerfully affective; while a contemporary recognition of the mutability and slipperiness of subjectivity finds an apt metaphor in the vanishing portraits, knowledge of the political disappearances in Muñoz’s native Colombia heightens its memorial qualities. William Kentridge’s animated drawing History of the Main Complaint (1996) utilizes erased and redrawn lines as an equally evocative metaphor for the amnesias and recoveries attending the history of apartheid in his native South Africa. In both cases the curators have shifted attention away from crucial socio-political contexts in order to emphasize the formal qualities of media. Their approach seems more appropriate for Jacco Olivier’s Almost (2009), a two-minute-long video in which layered panes of painted glass create a lush, ever-changing three-dimensional landscape, yielding unexpected configurations of time and space.

In contrast to these relatively archaic techniques, other works stretch the limits of available technologies to stage transformative exchanges between bodies and media. In the remarkable collaborative work After Ghostcatching (2010), specifically commissioned for the biennial, the real-time movements of dancer Bill T. Jones were recorded, drawn, animated, and rendered in 3-D by OpenEnded Group for the final eight-minute-long video. Angular lines roughly delineating bodies occupying a three-dimensional grid emerge from the black void of the screen. Jones’s voice directs the movement by calling out letters of the alphabet. As the letters give way to song and narration tinged with gothic horror, the figures seem to break out of their cubic strongholds. The seemingly infinite expanse of digital space is haunted by the organic body, which both mimics and exceeds the disciplinary effects of language. At the same time, viewers experience the body’s motions as though they are witnessing the cosmic birth of some alien creature, through the defamiliarizing effects of 3-D rendering.

As Lewis and Belasco emphasize, the technique of rotoscoping, or creating drawn animations from live-action footage, has much earlier roots. A related example is “Big Chief” Ko-Ko (1924), for which Max Fleischer traced the contours of the human body to create the outrageously stereotyped characters of a clown and a Native American.

Mary Reid Kelly’s You Make Me Illiad (2010), the only other work commissioned for the biennial, also engages in a rotoscope-like project of flattening the human form, but gains a dimension of ethical self-reflexivity. Kelly keeps the live-action footage of her own body, which has been painted white with black contours to emulate the flatness of cartoon characters and is punctuated, like old-time animations, with stop-motion dialogue frames. Kelly plays the role of a World War I German soldier who writes epic poetry, the Belgian prostitute he unsuccessfully solicits as his heroine, and an army official who delivers an outrageous lecture about the values of hygiene in military brothels. The wide-ranging and often hilarious expression achieved through Kelly’s use of rigid iambic pentameter underscores the subversion of historical roles that her characters perform. The video ends in tragic absurdity as the soldier-poet delivers his final line—“There’s no place like Homer!”—while succumbing to poison gas (not STDs). Kelly’s multi-layered work utilizes both antiquated and contemporary storytelling techniques to illustrate the ways in which imagined historical subjects assume relative flatness and density—a process that does not necessarily follow the arc of technological advancement.

Lewis and Belasco’s ambition was to extend the explorations of history, technology, and bodies taking place inside the work to the overall design of the exhibition. To this end, they hired architect David Adjaye to transform the rectangular former warehouse into an alchemical lab informed by different twentieth-century modes of viewing. The results were, predictably, mixed. In order to avoid the dominant black-box mode of displaying contemporary video, Adjaye had semi-transparent scrims installed in order to guide the viewer through a shimmering, interconnected projection space. According to the catalogue, the first of three color-coded sections is meant to invoke the “shadow-infused situations offered by the nickelodeon, mutoscope, and flip book,” but in fact consists of a couple of fairly standard rectangular spaces” (35). Next, a more radical configuration introduces viewers to the round, arena-like space of the postwar Cinerama. This collective viewing situation, where the works are meant to be “read like paintings,” threatens to become a bewildering vortex, where aimlessly wandering visitors and mixed soundscapes make it hard to hear or focus on anything, collective or otherwise. The difficulties of this space were intensified opening weekend, when the curators made a last-minute decision to switch artworks that was not reflected in the exhibition map handed out to visitors. In the final section, viewers are returned to a space that feels far more—perhaps too—comfortable: the intimate, one-to-one space of the personal screen. In addition to small rooms and wall installations, viewing stations lined up along a wall require visitors to sit and don headphones, as if in a computer lab. By turns wonderful and frustrating, the journey through three such markedly different spaces helps to focus attention on the spatial dynamics of viewing, which have their own particular history.

In The Dissolve, a tightly chosen body of works, a historical framework, and an experimental approach to exhibition design offer a complex picture of the relays between twenty-first century human bodies, subjectivities, and technologies. Still, in texts by Lewis and Belasco one catches an occasional glimpse of the Cartesian dualism of mind/body that has haunted new media studies. They write in the exhibition catalogue, for example, “we are in an aesthetic and cultural moment that prizes authenticity over theory and improvisation over formula” (22). Yet the work on display seems to call for a more nuanced telling of the ongoing sensory adjustments taking place in and through technologies, leaving neither body nor mind quite the same, a story that Anna Munster provides, for example, in Materializing New Media: Embodiment in Information Aesthetics (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2006). Lewis and Belasco conclude their essay by asserting, “technology becomes not an end, but, even more to the point, a means to more effectively enhance the sense of the authentic, the handmade” (38). Ultimately, the hand triumphs. What happened to alchemy?

Jessica L. Horton

Professor, Department of Art History, University of Delaware