- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

University of the Arts, Philadelphia

June 4–6, 2009 College Art Association.

Historically the book has served as a locus for the interaction of disparate forces. Dimensionally complex, it has been a place where material, cultural, structural, philosophical, temporal, mechanical, and aesthetic elements can encounter, react, assert, concede, proselytize, and reconcile. That the poet Charles Baudelaire can compare himself to a beggar nourishing his vermin while doing so in formal alexandrine meter, that the book can act in one moment as a container of authority and in the next as an agitator for change merely illustrate the interplay of forces at work within the book form.

What makes artists’ books different from other books is the degree to which they consciously embrace this potent tension and make explicit these encounters. By taking as their medium a form that has a rich history, but a freshness as an artistic medium, book artists have embraced a hybrid medium that can concurrently be both pregnant with associative possibility and yet free from conceptual constraints.

It is a wonder why conferences persist in adopting themes when presenters are typically inclined to focus on issues of their own concern rather than engage with the proceedings’ overarching topic or question. It was exceptional, therefore, the extent to which the participants in The Hybrid Book conference intently explored its proposed theme. Held in June 2009 at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, the conference combined an engaging program with a series of related exhibitions and a book fair in which artists showcased and sold their works.

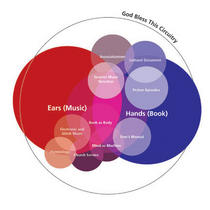

I found the most inventive presentation to be Tate Shaw and Andree Sallee discussing their book/audio collaboration, God Bless This Circuitry (2007). As members of the panel entitled “Intersection + Intermedia,” Shaw and Sallee created a presentation that was simultaneously a critical exploration of their collaboration and also a performance in its own right. Projecting an ever-growing Venn diagram of thematic concerns that ran throughout their book, Shaw and Sallee took turns describing the topics as they appeared. As the talk progressed, each began to speak before the other had finished, producing a visual and aural cacophony followed by intermittent bursts of clarity when one would grow silent before launching into the next section, thus allowing the other’s words to be heard in their entirety. The performance embodied their theme of how the various visual, textual, and aural components of God Bless This Circuitry intersect and vie for the reader’s attention, alternately gaining space in the reader’s consciousness and then receding as new elements interrupt the experience.

Another member of the “Intersection + Intermedia” panel, William Snyder III, explored hybridity through the intersection of art and political action. He described the history of 800,000 (2006), an installation, on exhibition during the conference, that consists of 800,000 pages bound into 2,500 books displayed in 100 crates. After learning about the genocide of 800,000 people in Rwanda, he went about establishing an orphanage and searched for a way to create art that could engage with these issues while making a tangible difference. He shed insight into the collapsing together of his missionary work and his artwork and how this drove his artistic decisions—from the materials he used, to his approach to participatory collaboration, to his use of art to fundraise for his missionary work (for a dollar one could purchase the experience of dipping one’s hand in mud and leaving a handprint on one of the book pages).

The last presentation on this panel was by the Canadian group SILLIS (Sequential Imaging Laboratory/Laboratoire d’imagerie séquenciel) who collectively investigate the intersection of media through the integration of lens-based image capture with digital processes. By far the most theoretical of the presentations, the members of SILLIS described their desire to hybridize the hybrid (mixing photogravure, which is already at the intersection of photography and printmaking, with digital processes). Exploring themes such as where intervention happens when combining different processes, they concluded with the radical assertion that the digital cannot exist without the analog, the latter of which will always have dominance over the former in the sensory realm.

The panel “Offset Applications: Then and Now” evoked the hybrid nature of the book, not within the individual presentations but through their juxtaposition. The panelists explored, from very different perspectives, the appeal of offset artists’ books, what brought artists to that medium, and what its future holds. Tony White began with framing remarks about the genesis of offset as an artistic medium, discussing early practitioners and how they described their activity, and citing Eugene Feldman’s phrase “painting with the press” and Phil Zimmermann’s rallying cry of “production not reproduction” as a way to distinguish the creative application of the offset press. Clifton Meador’s abstract, conceptual approach to explaining a production choice was then counterbalanced by Patty Smith’s delving into the material and technical passions that drove her choices.

Meador’s theme was ubiquity. The ubiquity of offset in the commercial world drove artists to use the medium for a different purpose. Meador argued that every technology represents a choice (to participate in one technology over another) and the inheritance of a set of values (the right and wrong way to do something, the role of that technology in the culture). Every process has its own syntax and every medium implies translation. But the ubiquity of four-color offset in advertisements creates the illusion of transparency and encourages a belief in its truth. So for Meador, the history of artists’ use of offset was the intentional subversion of this illusion, a manipulation of the medium (use of misregistration, false color, faked documentary photographs) as a means to draw the reader’s attention to it, thereby displacing its authority.

Smith then described her experience as an offset artist, framing her interest as a series of apparent contradictions and describing, with a fair amount of humor, her experiences as a woman trying to find her way in a historically masculine technology. Her own offset printing is more akin to traditional lithography—using hand-drawn imagery instead of the photography more common in offset. Smith let her visceral love of the medium shine through—the fall of the paper, the clattering of the machine, the need to throw your whole body into it. For Smith, the contradictions in the medium made it more appealing and allowed artists with very different aesthetics to collaborate. Smith then admitted the other appeal that drew so many early artists to offset: the ability to produce large runs economically, which has been lost on a current generation with printing technologies at their fingertips and a web to distribute works far and wide. Panel moderator, Amanda D’Amico, wrapped up with images of work that current students are doing with offset and offering a hopeful forecast for its future despite the decline in use by artists.

“The Reciprocity of Books and Digital Media” panel gave a glimpse into new directions in book art. Its moderator, Lori Spencer, posed three questions to each of the panelists: How have digital tools reshaped the relationship between author and reader? How have they affected what we think books are? And what do we see as the potential of the new media?

All three of the panelists focused on the interactive possibilities inherent in technology and how this provides book artists an opportunity to interact directly with their readers, whether in the creation of the work or in their encounter with it. Margot Lovejoy, for instance, creates works in which people can add text to a website that in turn becomes the basis for the piece. A significant feature of her approach is that her interactive website does not simply mimic the ubiquitous blog format where people add comments to a page but instead uses technology to transform the input into the final work of art. In her project CONFESS (2008), for instance, she developed a vocabulary of shapes to represent the types of confessions that people left on the site and thus created an interactive way to visually explore and react to each confession.

A recurring theme of this session, well articulated in Sue O’Donnell’s presentation, was that technology opens up possibilities for creating multiple versions of a work. Print-on-demand can be used to re-edition a limited-edition work, and websites and video can re-present book works in new media. Technology is being used to rethink the relationship between form and content and to understand a work as existing somewhere between all its various manifestations.

Pattie Belle Hastings concluded the panel with a highly speculative exploration of some of the intriguing possibilities new technologies could offer for creating books that act: GPS locative books, books that communicate with each other via RDIF chips, books that use EMFs to disrupt all cell phones near it; she persuaded us to believe the possibilities are endless.

The conference was wrapped up by Roberta Fallon and Anabelle Rodriguez who gave an outsider’s summary at the closing dinner. Both are involved in the art world but not the artists’ books world, and they offered a counterpoint perspective. What they found most refreshing was the book artist’s ability to speak with sophistication about their creative process while retaining an enthusiasm and modesty that is not prevalent in much of the art world. They both concluded that artists’ books need to become a more integrated part of that world.

Elisabeth Long

Co-Director, Digital Library Development Center, University of Chicago