- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Gerald and Sara Murphy were admired—adored—by many of the best-known members of the transatlantic avant-garde in the 1920s. John Dos Passos, their frequent guest both in Paris and on the Riviera, wrote happily of being “entertained . . . with great elegance and a great deal of gin fizz.” For Fernand Léger, Gerald was “the only American painter in Paris.” F. Scott Fitzgerald dedicated Tender Is the Night to them; the novel’s protagonists, the Divers, were modeled on the Murphys. Perhaps the best indicator of the breadth of their sparkling circle is a souvenir menu from a party they threw to celebrate the première of Igor Stravinsky’s ballet Les Noces in July 1923. The card was signed by, among others, Jean Cocteau, Pablo Picasso, Natalia Gontcharova, and Cole Porter—warm friends all.

The menu is one of many intriguing items featured in the exhibition Making It New: The Style and Art of Gerald and Sara Murphy. The Murphys’ story has been told often, and always with a sense of fairy-tale wonder. “Once upon a time there was a prince and a princess,” begins one friend’s account. Both Sara and Gerald had privileged upbringings: she was from a wealthy and socially ambitious Cincinnati family, spent many seasons in Europe, and was presented at the Court of Saint James. He was the heir to the Mark Cross fortune and educated at Yale, where he was voted “best dressed” and tapped for Skull and Bones. They met at an East Hampton party and were married in 1915. After Gerald’s desultory attempts to settle on a career, in 1921 they sailed to Europe where they found their true calling: the art of living.

It was a glorious time to be an American in Paris. As Dos Passos recalled: “Americans were rather in style in Europe in the 20s. Dollars, skyscrapers, jazz, everything transatlantic had a romantic air. [The Murphys] seemed the epitome of the transatlantic chic.” Their apartment in Paris was an ultramodern marvel. On their grand piano, instead of a sculpture, they mounted a gleaming ball bearing; in addition to bowls of flowers in every room, there were stalks of celery arranged in glass vases. The environment they created—both in Paris and, beginning in 1923, in their “Villa America” at Antibes—was exciting, witty, and, above all, generous. The adventurous, the creative, the brilliant, the fun-loving, all flocked to them. As Calvin Tompkins writes in his eloquent reminiscence in the exhibition catalogue: “They seemed to have known everybody who counted in the culture of the period” (7–8), and offered them hospitality, community, and support.

The Murphys were not just hosts to the creative outpourings of those years, they were participants. In addition to encouraging Stravinsky and other musicians, the Murphys collected jazz records and were noted singers of spirituals. They painted sets for the Ballets Russes with Gontcharova. Gerald and Cole Porter wrote Within the Quota, a riotous ballet (with sets and costumes by Gerald) detailing the adventures of a Swedish immigrant to New York. And after seeing paintings by Picasso, Braque, and Gris displayed in a Paris gallery, Gerald proclaimed: “If this is painting, then this is what I want to do.” He then embarked on a painting career that lasted seven years and yielded fourteen paintings (of which seven oils and a gouache survive). The imagery in these pictures was perfect for the machine age: turbines, watches, a razor, a cocktail shaker. Although Murphy never tried to sell the paintings, he exhibited several at the Salon des Indépendants—the 18-foot-tall Boatdeck being the most audacious, astonishing Parisians and provoking the resignation of selection committee head Paul Signac, who objected to the painting’s graphic boldness and overpowering scale. Other paintings were reproduced in art magazines; even Picasso expressed grudging admiration for Razor, proclaiming it, “Amurikin—certainly not European.”

But then, as explained by exhibition organizer Deborah Rothschild in her engagingly written biographical essay, “life intervened.” In short and horrifying succession, the Murphys’ younger son, Patrick, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The stock market crash required Gerald to return home to run Mark Cross. While Patrick, by 1934 in a sanatorium in upstate New York, was growing weaker, his brother, Baoth, developed meningitis and died in May 1935. Patrick died less than two years later. The golden times were over. The houses in Europe were closed; the paintings were rolled up and put away. For the rest of their lives the Murphys continued their pattern of connection and generosity with their friends, but much more quietly. Gerald never painted again.

Murphy’s paintings remained unseen until Douglas MacAgy, director of the Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts, showed them in the 1960 exhibition “American Genius in Review.” Since then, both the paintings and the personalities have been the subjects of insightful studies. There have been retrospectives at MoMA (1974) and Dallas (1986). The Murphys’ correspondence has been gathered by Linda Patterson Miller in Letters from the Lost Generation (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002). Calvin Tompkins’s New Yorker profile of 1962 (expanded and published in 1982 as Living Well Is the Best Revenge [New York: E. P. Dutton]) remains the most lyrical and evocative portrait of the Murphys’ years in France. Amanda Vaill’s 1998 biography Everybody Was So Young: Gerald and Sara Murphy—A Lost Generation Love Story (New York: Houghton Mifflin) is perhaps the first study to show how much Gerald’s extraordinary hospitality concealed nearly crippling self-doubt (as Fitzgerald perceptively noted, he kept “people away with charm”), and to discuss his agonized wrestling with what he called his “defect”—his homosexuality. In The Great American Thing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), Wanda Corn presented a stimulating portrayal of Gerald (and his painting) as the principal agent of the “Americanization of Paris.”

Making It New is the first exhibition to bring together both the paintings and the life—the “Art and Style of Sara and Gerald Murphy,” as the show’s subtitle has it. Its catalogue, with ten essays by painters, poets, musicologists, and literary and art historians, is also the most detailed account of their rich and multifaceted lives. This account is supported by ephemeral material that not only reveals the Murphys’ characters but also provides enchanting visual evidence of their centrality to the creative energies of their era. Through books, letters, papers, and photographs, we see them as hosts, as muses, and as creators themselves. Among the most charming of these mementoes is Gerald’s tiny letter to his infant daughter, and his note in a bottle sent to Sara. The packaging of the latter demonstrates his whimsy and the care he took with even the most prosaic details of life; the note’s poignant contents (“Let this commemorate the pain and tears of this night”) reveals his vulnerability. Similarly, the display of books dedicated to or including fictionalized portraits of the Murphys is an astonishing demonstration of their effect on writers of the era. The many photographs of the Picassos and the Murphys frolicking on La Garoupe beach, juxtaposed with works from the period by Picasso, makes clear the extent to which the Murphys entered his art. Although many of these connections have been made before, their impact is far greater in the aggregate. The exhibition also includes pictures that belonged to the Murphys—photographs by Man Ray, drawings by Léger—but no major works of art, for they owned none. Except for jazz records and some folk art, the Murphys were not collectors. They did not buy their friends’ works or solicit them as gifts. Their Man Rays and Légers were mementos: informal records of friendship and reminders that the Murphys were not patrons of the arts but participants.

The hazard in displaying so much material is that the Murphys emerge as dilettantes, and Gerald’s brilliant, original art becomes another token of their elegantly crafted lifestyle. Dos Passos protested this view: “There was a cool originality about his thinking that had nothing to do with the wealthy amateur.” The installation at Yale subtly shifts the balance of Making It New away from the biographical by dedicating the core of the exhibition space to works of art. There is plenty of Murphyana, to be sure: Yale’s installation includes cases of well-chosen photographs, letters, and other memorabilia, along with a slide show and two videos, but the emphasis is placed on the “art” rather than the “style.”

This emphasis makes the paintings by Picasso, Gris, Ozenfant, and others into an artistic milieu, and Murphy’s seven surviving oils and one gouache into an oeuvre. The result is a sense of visual excitement that justifies the faint air of celebrity worship generated by the letters and photographs.

Consistent with the exhibition’s biographical approach, Rothschild in her essay makes a compelling case for the oils as “concealed self portraits” (59). Yet to define them as such undervalues the extraordinary graphic power and ironic detachment that heralded a new kind of modernism. These are tough and witty pictures, brash in their scale and in their promotion of the mundane. The still lifes by Gris and others displayed nearby represent the kinds of pictures that inspired Murphy, while their brushy, elegant facture (so different from Murphy’s deliberately anti-virtuosic style) dramatize just how “Amurikin” his works were. These pictures are much more than an expression of Murphy’s coming to terms with his “emotionally barren” father. They are the first successful salvos in the transatlantic tussle for artistic supremacy that ultimately led to Pollock and other large-scale abstractionists, and to Pop.

Trevor Winkfield calls Murphy’s style “Exhibitionist,” and in his entertaining and stimulating essay on Murphy’s notebook, begins the kind of investigation the paintings deserve. He groups them by imagery: for example, the first paintings depict “maritime architecture” (surviving only in photographs, these works are reproduced actual size—or, in the case of Boatdeck, as tall as the Yale gallery’s ceiling height allowed). The notebook, on view in the center of the space dedicated to the oils, identifies subjects Murphy chose not to paint, and so provides another means for exploring the artist’s development. Both Rothschild and Winkfield note that Gontcharova taught Murphy to “think big and paint flat,” raising questions about what other stimuli—aesthetic and cultural—contributed to these paintings.

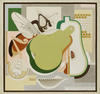

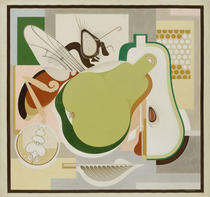

The last object in the exhibition is the painting Wasp and Pear (1929). Hung apart from the other works, it is an unsettling image. Murphy’s notebook entry for the picture—“hornet (colossal) on a pear . . . (battening on the fruit, clenched)”—prepares us for its intensity, but not for its distance from what has come before. The contrast with the neighboring Cocktail, so orderly and refined, is shocking. The label notes that “batten” also means “thrive at another’s expense,” and there is thoughtful speculation in the catalogue about the image as a reflection of Murphy’s emotional state. But Wasp and Pear displays a new, aggressive quality that begs for investigation beyond the psychological. It is hard to imagine what Murphy might have painted after this, or how his style, so redolent of the jazz age experience, could have reflected the post-Crash world.

Making It New is a fascinating portrait of the most glamorous and generous members of the Lost Generation, and of their extraordinary contributions to transatlantic culture. Of those contributions, Gerald’s enigmatic paintings remain the Murphys’ greatest legacy, and seeing them together makes clear that he was a painter above all. As his friend Archibald MacLeish said of him: “To any artist . . . the best revenge upon life, or more precisely upon death, is not living either well or badly but creating works of art.”

Carol Troyen

Kristin and Roger Servison Curator Emerita of American Paintings, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston