- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Conference. University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

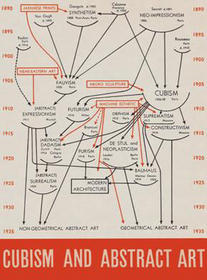

In 1936, for the cover of the Museum of Modern Art’s Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition catalogue, Alfred Barr famously created a flowchart of modernist movements fueling his two chosen strains of non-geometrical and geometrical abstraction. Barr’s recasting of history, which left out not only those modernist movements that did not fit his formalist history but also any mention of the contexts behind their success might be described as an example of what Van Wyck Brooks termed a “usable past.” In his 1918 essay appearing under that phrase, Brooks rejected the literary history of his day as the product of a “commercial philosophy” that offered little to the creative minds of the present (“On Creating a Usable Past,” The Dial [April 11, 1918]: 337–41). Recognizing that the past was a construct that “yields only what we are able to look for in it,” Brooks called for the discovery or invention of one more suited to contemporary writers’ goals. Barr’s internationalism would seem at odds with the politics of Brooks and other “Young Americans.” But a recent conference asserted that the period contemporaneous with his rise to power can profitably be seen as a laboratory for Brooks’s method.

The term “usable past” is widely employed these days without specific reference to its origins, but the organizers of this conference intended to call attention to Brooks’s ideas. “Usable Pasts?” brought together nine scholars from the United States and Great Britain to speak on American art from the interwar period. It was organized collaboratively between the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) to celebrate the revitalization of the study of American art history at Penn with the recent hires of Michael Leja and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw. Penn faculty member Christine Poggi and Visiting Professor Richard Meyer also played prominent roles, as did PMA curators Kathleen Foster and Michael Taylor. The conference drew an audience of close to one hundred people, many of whom were students, scholars, and curators from local institutions, suggesting that Philadelphia is reclaiming its historical status as a center for American art.

Brooks warned his readers that creating a “usable past” requires defining value in terms other than commercial and critical success. “What is important for us?” he demands, “What, out of all the multifarious achievements and impulses and desires of the American literary mind, ought we elect to remember?” In her welcoming remarks, Shaw quoted these last lines, calling the audience’s attention to the dual purpose of the conference. The conference sessions focused on how artists of the period under study defined their own heritages, but it went beyond that. Citing Brooks’s call for the creation of a new American past that was more attentive to the needs of an “unrealized present,” Shaw challenged those present to consider which legacies are or ought to be remembered to sustain our own work and push it forward.

Shaw is a student of Wanda Corn, whose 1999 book The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) outlined the importance of Brooks and his fellow cultural nationalists (such as Lewis Mumford, Waldo Frank, and Randolph Bourne) in framing American modernism of the interwar years. While few of the panelists made much out of these critics’ work, their themes overlapped with many of the issues they had raised, including the spread of industrialism, America’s engagement with international art movements, and the place of spiritual and emotional consciousness in modern art. At the same time, several panelists offered an image of pre-war modernism that corrected contemporary assumptions, particularly those fueled by the High Modernism of MoMA and Clement Greenberg in the years after World War II. Still others saw disturbing parallels between the nationalist ideologies and international ambitions at work then and now.

The invited scholars presented both new work and research that had already been published, the latter of which was recast in light of the conference theme. Talks were organized into three panels: “Long Distance Modernism,” “Engineering Aesthetics,” and “The Artist Inside and Out.”

The first session emphasized aesthetic dialogues taking place across geographic distances within the United States and between the United States and foreign countries. Joan Saab, from the University of Rochester, discussed the simultaneous promotion of Mexican art at MoMA and Macy’s department store in 1940, focusing on how both contributed to creating an image of Mexico as a vernacular American past that served the purposes of contemporary Pan-Americanists, in particular John D. Rockefeller Jr. Sarah Wilson of the Courtauld Institute of Art spoke next, offering a contextualization of Clement Greenberg’s seminal essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” in light of the extensive engagement between Partisan Review, in which it appeared, and Soviet art and policy. Wilson sees this as an example of the rich dialogue between American and European painting (both mural and easel painting) that took place during the interwar period, particularly through exhibitions at World’s Fairs. She then went on to explore other contemporaneous and subsequent European investigations of kitsch, arguing for the need to integrate these largely overlooked contributions to the modernist critical tradition. The session ended with a presentation on the correspondence between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz by National Gallery of Art curator Sarah Greenough, who is editing a book of these letters. Conducted most extensively during the years when the two were separate, with O’Keeffe first in Texas and, later, spending part of each year in New Mexico, the letters mixed comments on art and politics with frank expressions of sexual intimacy.

The second session undertook the question of how art responded to the technological and industrial developments of the era. It began with Andrew Hemingway from University College London, who presented a reading of two paintings by Stefan Hirsch, an artist who will figure in his book-length study of Precisionism and reification. Revealing the German-born artist’s debt to Arnold Böcklin, Hemingway characterized him as a “romantic anti-capitalist,” arguing that his work demonstrates how Precisionism was not necessarily as nationalist or pro-corporate as is commonly presented. Christina Cogdell similarly constructed a past that might support a contemporary critique of dominant economic and political forces. The College of Santa Fe professor traced the overlapping language, forms, and, sometimes, goals of the industrial designers behind streamlining and eugenicists seeking the biological improvement of the U.S. citizenry. While the talk focused primarily on research presented in her book Eugenic Design: Streamlining America in the 1930s (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), she linked it to her current research on the use of genetic and evolutionary research by contemporary architects. This session ended with a paper by Rice University’s Marcia Brennan on Marcel Duchamp’s use of the androgyne; her presentation drew from her current research on mysticism and the modern museum. Brennan described Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No. 2 (1912) and his cinematic restaging of the painting for Hans Richter’s 1946 film Dreams That Money Can Buy as androgynes—ambivalently gendered figures with the potential to disrupt notions of coherent corporeality and subjectivity. Identifying Barr’s flowchart as another androgynous formulation, Brennan suggested that the androgyne’s “unsaying” of gendered ideals opened up radically hybrid possibilities in the interwar years that are useful to return to today.

Gendered bodies were also central to the third session, which focused on artistic self-fashioning within emerging modernist art worlds. Kathleen Pyne, from Notre Dame University, returned to Stieglitz in order to explore his need for and characterization of a woman modernist, an inquiry that is the basis of her new book Modernism and the Feminine Voice: O’Keeffe and the Women of the Stieglitz Circle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). Pyne traced the primitivizing psychological and mystical discourses of sex prevalent in the intellectual milieu within which Stieglitz traveled. She argued that members of his circle, particularly O’Keeffe, self-consciously staged themselves in Freudian terms in their artwork and publications as a means of projecting a modernist subjectivity. While the Stieglitz set embraced sexuality as a means of garnering authority among Greenwich Village radicals, Left Bank lesbians attempted to legitimize their subjectivity by other means. As Yale University’s Tirza True Latimer argued, portraitist Romaine Brooks combined formal references to both modern art and classical antiquity to create a “modern Sapphic identity.” Reframing the argument presented in her book Women Together/Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), Latimer questioned the lasting value of this strategy for recording the presence (and absence) of lesbians in modern art history. Jacqueline Francis of the University of Michigan spoke next, presenting material from her forthcoming book on “racial art.” Shifting focus from the artist to her or his public, she looked at how critics sought expressions of ethnic identity in the work of artists perceived as racial others. Examining works by Max Weber (who renounced Cubism in favor of Jewish subject matter in the twenties), Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Malvin Gray Johnson, she proposed that the use of Expressionist style allowed each to destabilize the authority of the ethnic stereotypes they employed.

The advantage of constraining the topics to a relatively brief time period was that many speakers raised similar issues and discussed the same artists or even artworks. Barr’s flowchart came up several times, for example; and a number of speakers discussed Alfred Stieglitz’s career as an artist, critic, and impresario. One of the organizers admitted that the sessions could have been configured in multiple ways. The discussions that came at the end of each panel allowed for the development of themes that had been raised earlier, and a forty-five-minute plenary session at the end of the conference offered a welcome chance for panelists from all sessions to interact freely.

While it was exhilarating to see experts debate the significance of specific artworks, institutions, and events, the conference’s emphasis on methodology also produced a stimulating discussion of current practice that included substantial contributions from audience members. Early on, Kathleen Foster proposed that the presenters might be understood as entering the debate about “near” and “far” approaches to scholarship that was the topic of a session (organized by Pyne) at the College Art Association’s most recent conference. In thinking through the meanings of these terms, it is useful to observe that some presenters focused closely on objects or specific artists while others looked at cultural politics within and beyond the art world, and that both of these approaches prompted discussion. Of particular interest to those present was the question of the place and character of biographical information in contemporary critical writing. The impact of O’Keeffe’s relationship with Stieglitz on both the production and promotion of her work is undeniable, but some questioned the implication of publishing their intimate correspondence, the explicitness of which can fuel a sensationalism that might detract from more productive kinds of inquiry. Greenough responded confidently to this challenge by stating her reluctance to edit out passages of the couples’ letters, suggesting that not only would this lead readers to be curious about what was left out, but also that it is important to see how fluidly the artists moved between different subjects. The question of near and far views is often read as a reflection of a scholar’s academic politics (close views belong to formalists, far ones to people who care about the power dynamics of visual culture), but “Usable Pasts?” complicated this view. Asking why intimate biography is common in scholarship on O’Keeffe and Stieglitz and problematic in assessing Rauschenberg and Johns, Meyer suggested the potential value of methodological mixing. Similarly, the scholar most attentive to a close reading of imagery was Hemingway, who used it to support an argument about cultural politics.

The conference theme forced viewers to also think of near and far in chronological terms. As many of the presenters pointed out, our contemporary context may demand different constructions of the historical projects of the interwar years than those created by people living in that time. While it is instructive to confront how, for example, racialist ideology and scientific determinism still influence our thinking, it is also necessary to understand the alterity of the past. This became most apparent in discussions of aesthetics. As the papers made clear, there are many works that were highly regarded in the interwar years that have not made it into the canon and whose aesthetic merits are not immediately recognizable to contemporary viewers. While it is a common belief that aesthetic value is culturally constructed, the issue of “good” and “bad” art nevertheless came up. Cogdell admitted loving streamline design despite her familiarity with its eugenicist politics. Similarly, Meyer asked what it means that today some of us find Weber’s cubist paintings, which were rejected by his peers, so much more interesting than his genre pictures of Hasidic Jews, which were deemed more aesthetically pleasing. Is the only answer the one given by Francis: that we are victims of modernism? Or are there different ways to understand the pleasure, or lack thereof, attending our encounter with objects from the past? As scholars and teachers recover the historical contexts of American art (the far), should we also encourage our audiences to explore how and why we are drawn to them today? The question brings us back to Brooks’s notion of history itself as an aesthetic object, the contemplation of which inspires our creative and critical work.

Brooks had the notion that American writers constituted a “brotherhood” that would be unified through his recovery of literary history. Barr’s flowchart was similarly constructed to create a cohesive field of artistic practice. As the diverse methodologies and opinions expressed in Philadelphia attest, American art history is not a coherent field. Nevertheless, the collegiality expressed over two days was admirable, and was facilitated by the careful planning that went into making this conference run smoothly. Much of this was due to the work of staffers at Penn and PMA, in particularly Penn PhD candidate Ellery Foutch. The success of “Usable Pasts?” was also facilitated by the financial support of the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Hyde Foundation, as well as PMA and several departments and programs at Penn.

Elizabeth Hutchinson

Assistant Professor, Department of Art History, Barnard College/Columbia University